The rise of modern science, accompanied by its many technological triumphs, has led to widespread acceptance among intellectual elites of a worldview that conflicts sharply both with everyday human experience and with beliefs widely shared among the world’s institutional religions.

Most contemporary psychologists, neuroscientists, and philosophers of mind, in particular, subscribe explicitly or implicitly to some version of “physicalism,” the modern philosophical descendant of the “materialism” of previous centuries. On such views all facts are determined by physical facts alone.

We human beings are thus nothing more than extremely complicated biological machines, and everything we are and do is explainable, at least in principle, in terms of our physics, chemistry, and biology – ultimately, that is, in terms of local interactions among self-existent bits of matter moving in accordance with mathematical laws under the influence of fields of force.

Some of what we know, and our capacities to learn more, are built in genetically as complex resultants of biological evolution. Everything else comes to us by way of our sensory surfaces, through energetic exchanges with the environment in ways already largely understood. All aspects of mind and consciousness are generated by (or in some mysterious way identical with, or supervenient upon), neurophysiological processes occurring in the brain.

We are “meat computers” in Marvin Minsky’s chilling phrase, or “moist robots” in its Dilbert parody. Mental causation, free will, and the self are mere illusions, by-products of the grinding of our neural machinery. And since mind and personality are entirely products of our bodily machinery, they are necessarily extinguished, totally and finally, by the demise and dissolution of the body.

There can be no doubt that this bleak vision continues to dominate mainstream scientific thinking. It has contributed to the “disenchantment” of the modern world with its multifarious ills. It has also driven a progressive erosion of traditional forms of religious belief.

Indeed, recent years have witnessed a series of all-out attacks on religion by well-meaning defenders of Enlightenment-style rationalism such as Richard Dawkins and Daniel Dennett, who clearly regard themselves and current mainstream science as reliably marshaling the intellectual virtues of reason and objectivity against the retreating forces of irrational authority and superstition.

For them the truth of physicalism has been demonstrated beyond reasonable doubt, and to think otherwise is necessarily to abandon centuries of scientific progress, unleash the black flood of occultism, and revert to primitive supernaturalist beliefs characteristic of bygone times.

Not everyone shares these sentiments. I, for one, represent a long-running intellectual fellowship, organized in 1998 by Michael Murphy under the auspices of Esalen’s Center for Theory & Research (CTR), whose members take a starkly different view: We think it requires astonishing hubris to dismiss en masse the collective experience and wisdom of a large proportion of our forebears, including persons widely recognized as pillars of all human civilization. We believe that the single most important task confronting modernity is that of a meaningful reconciliation of science and religion.

I hasten to add that for us any such “reconciliation” involves much more than simply segregating science and religion into hermetically sealed “magisteria” where they can go their separate ways in uneasy coexistence, as originally decreed by Descartes and recently advocated again by the evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould.

Rather, we believe that emerging developments within science itself are leading inexorably toward an enlarged conception of nature, one that can accommodate realities of a “spiritual” sort while rejecting rationally untenable “overbeliefs” of the sorts targeted by critics of the world’s institutional religions.

We advocate no specific religious faith, and we aspire to remain anchored in science while expanding its horizons. We are attempting in this way to find a middle path between the polarized fundamentalisms – religious and scientific – that have dominated recent public discourse. Both science and religion, we believe, must evolve.

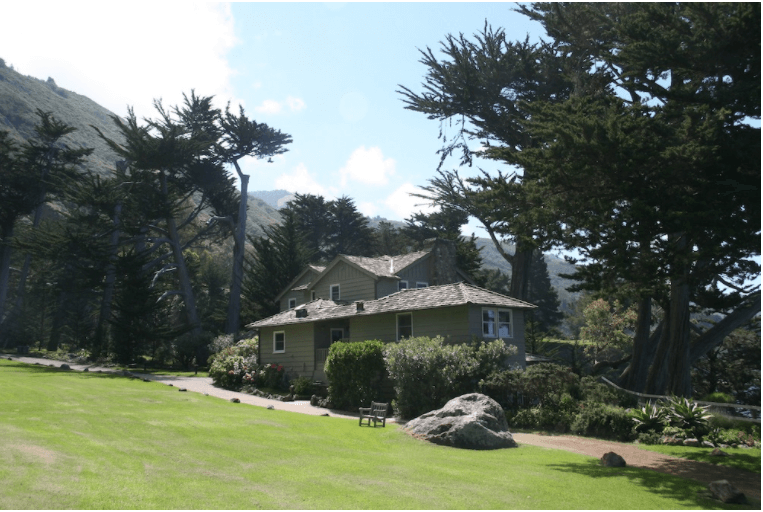

Over the 15-year duration of the project, our work involved over 50 participants in toto, roughly 20 of whom were active during any given year. Each year we organized an intensive 5-day face-to-face meeting of the currently active members in the magnificent ambience provided by Esalen, supplemented by occasional smaller meetings in San Francisco or elsewhere.

Our membership has always been uncommonly diverse, including physical, biological and social scientists, scholars of religion, philosophers, and historians of science among others.

But in general terms we are scientifically-minded adults with broad interests who think of ourselves as “spiritual” but not “religious” in any conventional sense, and who are skeptical of the currently-prevailing physicalist worldview, but equally wary of uncritical embrace of any of the world’s major religions with their often conflicting beliefs and decidedly mixed historical records.

We focused initially on the question of post-mortem survival. As Mike Murphy had clearly recognized, this is a watershed issue theoretically, because survival beliefs are common to traditional faiths but cannot be true if physicalism is correct.

Furthermore, there already exists—largely unknown to believers, skeptics, and the general public alike—a sizeable body of high-quality evidence suggesting that survival does at least sometimes occur.

We quickly realized, however, that our task was really much larger, and that we needed to approach it in two overlapping stages: first, to assemble in one place many lines of peer-reviewed evidence demonstrating empirically the inadequacy of conventional physicalism; second, and far more challenging, to seek some better conceptual framework to take its place.

The first stage culminated in the publication in 2007 of Irreducible Mind: Toward a Psychology for the 21st Century (Kelly, Kelly, Crabtree, Gauld, Grosso, & Greyson; henceforth IM). Topics addressed include paranormal (“psi”) phenomena; manifestations of extreme psychophysiological influence such as stigmata and hypnotically induced blisters; prodigious forms of memory and calculation; psychological automatisms and secondary centers of consciousness; near-death and out-of-body experiences, including experiences occurring under extreme physiological conditions such as deep general anesthesia and/or cardiac arrest; genius-level creativity; and mystical-type experiences whether spontaneous, pharmacologically induced, or induced by transformative practices such as intense meditative disciplines of one or another sort.

Collectively, these phenomena greatly compound the explanatory difficulties posed by everyday phenomena of human mental life such as meaning, intentionality, the subjective point of view, and the qualitative aspects of consciousness—all topics that have recently been targets of intense philosophical discussion.

In a nutshell, IM added a rich empirical dimension to what appears to be a rising worldwide chorus of theoretical dissatisfaction with classical physicalism as a formal metaphysical position. We seem to be at or very near a major inflection point in modern intellectual history.

Classical physicalism is definitely inadequate, but what should take its place? We addressed this far more difficult question, the main target of the second phase of our project by struggling to understand how we individual human beings and the world at large must be constituted such that “rogue” phenomena of the sorts catalogued in IM can occur.

On the psychological side we were already committed to what historically have been called “filter” or “transmission” or “permission” models of the brain/mind relation. As developed by the great pioneers of Psychical Research, F. W. H. Myers, William James, and Henri Bergson, such models portray the brain not as the generator of mind and consciousness but as an organ of adaptation to the demands of life in our everyday environment, selecting, focusing, channeling, and constraining the operations of a mind and consciousness inherently far greater in capacities and scope.

A central aim of the first phase of our project had been to review and re-assess Myers’s model of human personality in light of subsequent research, and we had found that the evidence supporting such pictures has actually grown far stronger in the century following his death. Myers and James themselves were soon pushed aside by the rise of radical behaviorism with its self-conscious aping of the methods of classical physics, and that influence persists in modified form even now in mainstream cognitive neuroscience.

In our view psychology has taken a hundred-year detour, and is only now becoming capable of appreciating the theoretical beachhead that our founders had already established.

The normally hidden region of the mind—Myers’s subliminal consciousness or “The More” of William James—is the wellspring of the latent human potentials that have historically comprised Esalen’s main practical focus.

But it is also precisely these transpersonal aspects— especially psi phenomena and mystical experience with their deep historical and psychological interconnections, postmortem survival, and genius in its highest expressions—which jointly demonstrate that classical physicalism must give way to some richer form of metaphysics.

For me personally the first phase of our project went a long way toward dissolving what the great American psychologist Gardner Murphy long ago called the “immovable object” in the survival debate—the biological objection to survival: Specifically, if physicalism is true, and mind and consciousness are manufactured entirely by neurophysiological processes occurring in brains, then survival is impossible, period.

But the evidence we assembled clearly shows, I believe, that the connections between mind and brain are in fact much looser, and can be conceptualized in the alternative fashion of filter or transmission models without violence to other parts of our scientific understanding, including in particular leading-edge neuroscience and physics (see especially IM Chapter 9).

That in turn invites—in fact demands, we believe—a more radical overhaul of the prevailing physicalist metaphysics. Note that what is at issue here is not whether we will have metaphysics—because we inevitably will, whether we are conscious of it or not—but whether we will have good metaphysics or bad.

As we began to approach these larger metaphysical issues, we recognized that a central element of our strategy should be to bear down on conceptual frameworks both past and present that explicitly make room for rogue phenomena of the relevant sorts. To that end, philosopher Mike Grosso began systematically surveying the long and illustrious intellectual history of such conceptions, focusing mainly on Western thinkers from pre-Socratic philosophers up through Myers, James and Bergson, and then on to more recent figures like C. D. Broad, Cyril Burt, and Aldous Huxley.

We recruited a number of new members with especially relevant skills and interests. These include a number of scholars of religion who specialize in relevant forms of mystically-informed religious philosophy: Paul Marshall (author of several excellent books on mysticism, who helped us understand more fully why and how mystical experiences, although widely ignored or disparaged in our Western scientific tradition, provide crucial pieces of the metaphysical puzzle), Greg Shaw (a specialist in the Neoplatonic tradition), Ian Whicher (Patanjali and the yogic tradition), Loriliai Biernacki (the 11th-century Kashmiri Tantric philosopher/sage Abhinavagupta.), G. William Barnard (a student of comparative religion and author of books on James and Bergson), and Jeff Kripal (another comparativist, and co-director with Mike Murphy of the Center for Theory & Research).

We approached this comparative material, of course, not with the expectation that any of these ancient systems contained all the answers, but in the interest of prospecting for common themes and useful clues as to how best to advance our theoretical purposes.

We also invested considerable effort on relevant parts of the Western metaphysical tradition. Paul Marshall, for example, has continued to develop his long-gestating “monadic” theory, modified from Leibniz’s original version so as to improve its power to explain the relevant phenomena.

In addition, Adam Crabtree launched an in-depth investigation of the contributions of James’s friend and colleague Charles Sanders Peirce, who took both psi and survival seriously and believed his metaphysics could explain them.

Eric Weiss further elaborated his “transphysical process metaphysics,” which combines an updated version of Whitehead with insights derived from the modern Tantric philosopher/sage Sri Aurobindo.

In keeping with our general orientation we have also sought contributions from the scientific side. Neurobiologist David Presti and I, for example, have examined filter or transmission models from a psychobiological point of view, concentrating on psi, flights of genius, and mystical experiences as primary expressions of the deeper resources of the psyche. What sorts of brain conditions permit or actively encourage access to these resources, and why?

We also recruited several prominent physicists including Henry Stapp, who presented his general quantum-theoretic model of the mind/brain connection and began exploring its possible extensions to rogue phenomena including psi and survival.

Harald Atmanspacher, another quantum theorist, informed us about the Pauli-Jung dual-aspect monism, and showed how it leads naturally to a theoretical taxonomy of exceptional experiences matching those actually occurring in clinical practice. And Bernard Carr, a cosmologist and former president of the Society for Psychical Research, provided expositions of his own and other forms of hyperdimensional theory, again emphasizing their compatibility with leading-edge science (in this case relativistic science and string theory) and their potential to help explain phenomena such as psi and survival.

All of these efforts recently culminated in a second book, Beyond Physicalism: Toward Reconciliation of Science and Spirituality (Kelly, Crabtree, & Marshall), released in February by Rowman & Littlefield.

Our collective sense is that theorizing based upon an adequately comprehensive empirical foundation that includes our rogue phenomena—especially psi, survival, and mystical experience—leads inescapably into metaphysical territory traditionally occupied by the world’s major institutional religions.

Specifically, we argue that emerging developments in science and comparative religion, viewed in relation to centuries of philosophical theology, point to some sort of evolutionary panentheism as our current best guess about the metaphysically ultimate nature of things.

Panentheism attempts to split the difference between classical theisms and pantheisms, conceiving of an ultimate consciousness or God as pervading or even constituting the manifest world, as in pantheism, but with something left over, as in theism. The version we tentatively embrace further conceives the universe as in some sense slowly waking up to itself through evolution in time.

Most importantly, the rough first-approximation picture we develop can be elaborated and tested through many kinds of further empirical research, especially research on meditation and psychedelics as pathways into higher states of consciousness. Although a great deal remains to be done both theoretically and empirically to narrow the class to its most viable member(s), we feel confident that we are headed in the right direction.

We see evolutionary panentheism more generally as an emerging metaphysical vision—a “stealth worldview”—that integrates the philosophical lineage of German idealists such as Fichte, Schelling and Hegel with the common deliverances of the world’s mystical traditions and with the incipient expansion of science itself as previewed in IM.

Our emerging panentheism offers an expanded scientific worldview that can embrace empirical realities of spiritual sorts while remaining faithful to science. This synoptic vision seems to us to harbor tremendous practical implications—its “cash value”, as William James would say—in providing humanity with an ethos that is fundamentally life-affirming and optimistic, profoundly ecumenical in character, and potentially capable of addressing a multitude of societal ills and threats to our precious planet that can be seen as flowing directly or indirectly from the currently dominant physicalism.

What is ultimately at stake here seems nothing less than the recovery, in an intellectually responsible manner, of parts of our human cultural heritage that were prematurely discarded with the rise of modern science starting four centuries ago. Especially significant at this critical juncture, and the fundamental new factor that we think will finally allow this recovery to succeed after numerous previous failures, is that it is now being energized by leading-edge developments in science itself.

This essay is adapted with permission from an article that appeared in EdgeScience 22, June 2015, published by the Society for Scientific Exploration (http://www.scientificexploration.org).

Edward F. Kelly is a Visiting Professor in the Division of Perceptual Studies (DOPS), a research unit of the Department of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences at the University of Virginia, and President of Cedar Creek Institute, an affiliated non-profit research institute.

He received his Ph.D. in psycholinguistics and cognitive science from Harvard in 1971, and spent the next 15-plus years working mainly in parapsychology, initially at J. B. Rhine’s Institute for Parapsychology, then for ten years through the Department of Electrical Engineering at Duke, and finally through a private research institute in Chapel Hill.