Be yourself; everyone else is already taken. — Oscar Wilde

I grew up in the 1950s and ’60s in a hardworking, middle-class community in Newark, New Jersey. During my first five years of life, we shared a duplex with my grandparents, my mom’s parents. Then, thanks to a GI home loan, my dad moved us to a four-bedroom house in the Weequahic section of Newark, one block away from our grammar school and three blocks from the high school. We had a driveway and a backyard with enough space for a basketball hoop on the garage. My brother and I were in heaven. We had one black-and-white television set with four working channels. Most Sunday nights we’d pile into our family car to drive to Uncle Marty and Aunt Ethel’s house to watch The Ed Sullivan Show in color. We had two telephones: one was downstairs on the wall in the kitchen, and the other was upstairs in my parents’ room. My parents shared a car, and my brother and I had bicycles, which was how we got everywhere we wanted to go. We didn’t have much, but neither did anyone else.I had a great crew of friends, and everyday — rain or shine — we played in the streets or in the playground after school.

Everyone was trying to make something of themselves. My father was a fiercely hardworking guy who wanted to be successful. For him, work wasn’t about “finding his bliss,” it was about being a responsible husband and father. His dad had skipped out on him, his brothers, sister, and mother for almost ten years during the Depression. In contrast, my dad wished to be a reliable family man. He wanted our family to be living the American dream. Neither of my parents had gone to college, but neither did the parents of most of my friends.There wasn’t a need or desire for excess; if anyone had it, we certainly weren’t exposed to it. The kids on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand coming out of Philly looked and acted a lot like my friends, who were a cross between the characters in Grease and Diner.

As a teenager,I was a normal, reasonably well-adjusted kid and a conscientious student, getting all As throughout high school. I was also a pretty good athlete. I was captain of the tennis team, and my friends and I played a lot of basketball. Our Jewish Community Center (JCC) basketball team — comprised of many of my best buddies — won the state tournament, then the regional, then we took first place in the national championship. Competitive team sports were, without a doubt, the master narrative and favorite part of my growing-up years.

The rules of life were simple, almost two-dimensional. There wasn’t any talk about personal feelings or identity, self-actualization, discovering your passion, or mental health. I didn’t do much deep thinking about anything. No one I knew did. The most famous person from our neighborhood, Philip Roth, was a decade or two older than me. When he first achieved fame as a writer and storyteller, it was with a book about a guy who masturbated all the time. I didn’t have much perspective or insight about my life’s path. I figured I’d go and get a degree, start a career as an electrical engineer or physicist, fall in love, get married, have children, and live in a house within a few minutes of where my mom and dad lived. So I went to a fine engineering school at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. I partly went because they accepted me on early notice, and it was a good school, and also because I could be on a bus to get home for a visit in around two hours. During my first two years, I jumped wholehog into science. In truth, I didn’t enjoy it very much. I didn’t particularly like the classes, the homework, or the professors. Living in a dorm and then in a frat house — on an all-male campus with our sister school, Cedar Crest, a half hour away — we had a truly stilted social life. In the larger world, the sexual revolution was awakening and protests to the Vietnam War were erupting everywhere. I got drunk on most weekends and tried pot, but my state of mind remained relatively plain vanilla and middle of the road. Overall, my grades were fine, and I was making progress toward adulthood, albeit feeling somewhat uninspired.

In my junior year, I had to take some electives. My curriculum advisor suggested I take a social science course to round out my engineering and physics training, so I wandered into a psychology course being taught by a cool young professor (every campus had one). It was 1969,and I honestly didn’t even know what psychology was. The professor, Dr. Bill Newman, had recently graduated with his PhD from Stanford, so he’d been living in the San Francisco Bay Area. At that time, before the Palo Alto peninsula became Silicon Valley, it was the home of Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, Jerry Garcia, and a whole new drug-fueled bohemian culture. Dr. Newman was smart, fun and hip, very unlike my physics and chemistry professors, who were quite square. The course was titled “The Psychology of Human Potential,” and from the first lecture, it absolutely blew my mind. It was based on the idea that human beings have extraordinary capabilities — vast mental, physical, and even spiritual potential — and that we were only tapping into maybe five percent of it. There was also the suggestion that our modern educational and physical training programs were quite pedantic and designed to activate only a tiny portion of our capabilities. This point of view completely turned me on and excited my imagination more than anything I had ever encountered. It occurred to me that there was a multicolored worldout there, yet I was trapped in the black-and-white anteroom. The first textbook of the course was The Varieties of Psychedelic Experience by psychologists Robert Masters and Jean Houston, and the second was Psychotherapy East and West by philosopher Alan Watts. The third was Toward a Psychology of Being by breakthrough “self-actualization” thinker Abraham Maslow, and the fourth was a book by Dr. William Schutz called Joy, about the exaltation one feels when one breaks free of restrictive and confining patterns. All these books were recently written, filled with big ideas, and, for me, mind-blowing.

As I dug deeper and deeper, I learned that there were ancient therapies and practices such as meditation, tai chi, and yoga that could unleash these potentials. I learned about many emerging new approaches, including bioenergetics, Rolfing, encounter groups, and Gestalt therapy, that were designed to loosen mental and physical constraints and liberate people to live a bigger, grander version of their possibilities. I immediately started practicing beginner’s yoga and meditating. I also gathered some of my electrical engineering friends to build simple biofeedback equipment with which we attempted to alter our brain waves while in sensory-deprivation chambers. I went to the library and started gorging on everything I could find that probed the search for human potential: Ram Dass’s Be Here Now (a Xeroxed copy of the manuscript), P. D. Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous, Alexander Lowen’s The Betrayal of the Body, and Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha, to name a few. Over my life, I have heard people tell stories of their awakening sexuality, or their discovery of their personal passion for playing the piano, or even their realization of God. For me, this was like my previously dormant volcano of curiosity had exploded. Who am I? How does my mind impact my body? Do I have any superpowers? If so, what are they? Does my brain contain all of my mind? Is there a God, and if so, what’s his or her plan? Am I reincarnated, and if I am, what other lives have I lived? Are humans done evolving? Evolving to what? What is my purpose? Do I have a destiny? Questions poured forth unrelentingly. I had never really experienced angst before, but I was swimming up to my eyeballs in it now. I knew I had to find answers.

I couldn’t help but notice that in the human potential authors’ bios, the name Esalen came up time and again: Alan Watts is a teacher at the Esalen Institute or William Schutz left Harvard to be a teacher at the Esalen Institute, or Fritz Perls teaches workshops at the Esalen Institute. The pursuit of human potential became my singular focus, and I knew I couldn’t get enough of the real deal in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. I abruptly decided to drop out of Lehigh and go to the source of this revolution — California, specifically, the Esalen Institute perched atop the mysterious cliffs of Big Sur. This decision surely didn’t make my mom and dad happy. They thought my mind had become unhinged and they were losing their fair-haired, all-American boy.

I sold everything I had and cut into my bar mitzvah money and the meager savings I had accumulated from my summer jobs to pay for the workshops I was going to take at Esalen. I imagined that five months at Esalen would be kind of like a semester at college. So, very innocently, I signed up for five months of nonstop workshops.

When the day arrived for me to fly west, I said goodbye to my family. My brother, Alan, who was three years older than me and a straight arrow, was bewildered by the whole thing. My mom was, as was her nature, encouraging but nervous. When my dad said goodbye, he broke down and sobbed — something I had never seen him do before.

I took off from Newark Airport, bound for San Francisco. I had never been farther west than Pennsylvania. Upon landing, I had only to begin walking through the terminal to be immediately entranced by the Summer of Love look, style, and attitude that made California feel so completely different from New Jersey. There were so many young people, and they were so attractive, so seductive.

Esalen had a van that picked me up in San Francisco for the drive to Big Sur. Inside were two women and an older man, both heading to their first Esalen experience. Soon enough, my new friends and I were on the way through the gorgeous terrain. I kept the window open so I could feel the cool ocean air. It was a ride unlike any I had ever taken. As we passed Monterey Bay heading south, an unending cascade of massive mountains rose up to my left, while the highway began to lift me above sea level on the precarious edge of a winding cliff to my right that plummeted to craggy rocks and the tempestuous Pacific Ocean below. Having grown up near the Atlantic, with its flat beaches and pulsing shoreline waves, I could not believe the primitive strength and rugged beauty of the Big Sur Pacific coastline.

For the next hour, there were countless hairpin turns, each one revealing a panorama of the Santa Lucia Mountains meeting coastline more incredible than the one before. All along the route we spotted tourists who had precariously parked their cars on the narrow shoulder to snap a few breathtaking photos, and hippie boys and girls thumbing their way to who knows where. Out at sea, we caught glimpses of whales breaching. At one point the van driver whispered over his shoulder to his spellbound passengers, “This is why it’s called God’s country.”

And then, about fifty winding miles south of Monterey, on the ocean side of the road, a modest wood sign, which still exists today, declared ESALEN INSTITUTE / BY RESERVATION ONLY.

We had arrived. I had arrived.

The van pulled down the steep driveway to reveal an Eden-like campus with a sumptuous vegetable garden unlike anything I had ever seen. I might as well have just landed on an alien planet. We jumped out to register in the Esalen office, staffed by beautiful hippie women and men. Around the fourteen-acre property, gorgeous rock formations were swarmed by flowers, a great hall served as a communal dining room, a spectacular canyon with waterfalls contorted among cypress trees, and, of course, a natural hot spring was filled to the brim with naked folks laughing, playing, or staring out across the ocean.

(Fast-forward many years: in 2015 my wife Maddy and I are watching one of our favorite TV shows when its protagonist arrives on Esalen’s mysterious cliffs, seeking answers to his own inner turmoil and to his curiosity about where pop culture is heading. Turns out that the last episode of Mad Men sends Don Draper to Esalen, an end point that is actually a beginning. Draper’s arrival takes place in exactly the same year and season when I was first there — although I don’t recall meeting him at the time!)

That first day, I found my way to my shared room and unpacked. I ate alone in the cafeteria-style dining hall, mesmerized by the truly amazing sunset over the Pacific. Soon after, I walked up the hill to a funky building where I’d be joining my first workshop. It was an “encounter group” led by the renowned Dr. William Schutz, the Harvard professor who had dropped out of academics and invented encounter groups. Schutz had gravitas at Esalen. He had recently published his controversial book Joy, and with the popularity of the 1969 movie Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, which playfully spoofed one of his Esalen workshops, Will Schutz appeared on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson many times demonstrating trust exercises with other guests and declaring the need for everyone to get open and honest and tell the truth about what they were feeling. During this anti-establishment period — fueled on the one hand by antiauthoritarian political protests and on the other by the sensuality and freedoms being espoused by a new era of sex, drugs, rock and roll, and mind expansion — Schutz and many others felt it was a time for a new psychology.

In addition to having taught traditional psychology at Harvard, Schutz had recently trained with Ida Rolf to become a Rolfer. Because he and Fritz Perls both lived and taught at Esalen, Schutz picked up many of Perls’ Gestalt therapy insights and techniques. He was also fascinated by the work of Wilhelm Reich, Moshe Feldenkrais, and J. L. Moreno — and he combined all those different modalities into a new kind of therapeutic dynamic, which he called an “encounter group.” Depending on how you looked at his approach, it was either a brilliant synthesis of numerous mind-body therapies or a zany, touchy-feely mash-up — or possibly both.

The encounter group movement aimed to achieve personal openness, honesty, and realness by stripping away the façades, unpeeling the armor, and uncoiling the usual defenses. No need for pretense or cover-ups: if you’re hurting, be hurting. If you’re angry, be angry. If you’re deeply sad, let it out. If you’re jealous, talk about it. Before then, most psychotherapy was done one-on-one for an hour or so in the privacy of a therapist’s office. And it could take years for a breakthrough to happen.

Encounter groups busted that wide open. First, let’s remove the privacy and make therapy into a group thing. To be sure, that was a wild idea. Some of the impetus for that came by way of AA recovery groups and from drug rehab programs such as Synanon. In England, T-groups and sensitivity training were gaining popularity. Second, let’s use these groups to break people out of their uptight, middle-class lives of the 1950s and’60s, where everybody was trying to keep up with the Joneses and people weren’t willing or even able to share their true feelings. That was a key theme: Aside from your thoughts, what do you feel? “What do you really feel?” the group leader would ask. And most people would respond, “What do you mean? What is a feeling?” The idea was that you can know yourself more truly if you are in touch with your feelings.

Psychotherapists around the world were fascinated by these intensive new modalities, and they flocked to Esalen. Thanks to extensive media coverage, New York intellectuals, Hollywood creatives, and midwestern ministers also found their way to Eslaen. A writer might be working on a screenplay one day in her office in Weehawken, New Jersey, and then the next day be flying to California, to be in a room with twenty strangers—all of whom would be getting down into their raw issues, no holds barred. Directors, actors, all manner of artists, and voyeurs flocked to these sessions because they resembled the techniques being used in actor training. You know, feel what it’s like to be a sexually promiscuous woman with schizophrenia, or feel what it’s like to enraged by fear and jealousy. It was believed that there was a truer version of one’s self buried under the armor, under the façade. People came to drop out, turn on, and tune in.

Back to my first evening at Esalen. Dinner was over, the sun had set, and it was eight o’clock on a Friday night in early September 1970. I was twenty years old. A few months before, I had been an engineering student at all-male Lehigh University. I took off my sandals and entered the room for my first workshop. The room was carpeted, and there was no furniture other than colorful oversized pillows arranged in a tribal circle. I took a seat/pillow, looked around, and suddenly felt very, very young. People were forty, fifty, seventy years old. Being the early moments of the hippie era, most of the guys had muttonchop sideburns and bell-bottoms, and the women were braless and adorned with assortments of beads and headbands.

The group leader, wearing a Harry Belafonte–style dashiki, introduced himself not as Dr. Schutz or Professor Schutz but simply as “Will.” Then with no further pomp, circumstance, or introductions, he invited us to “stand up and silently walk around the room and touch people wherever you wish and look into their eyes.” And that’s exactly what everyone did. Before I knew it, I was being touched in exploratory ways on my face, my chest, my thighs, and everywhere else by both women and men. What?

A short fifteen minutes into that, Will said, “Okay, now I want you all to go outside the door, remove all your clothes, and then come back into the room and find the person to whom you’re least attracted and sit in front of them and tell them why.” Do what? I was terrified. This is fucking nuts! I thought. What the hell have I gotten myself into? I thought of walking out the door and worming my way back to New Jersey. But curiosity got the better of me and I steadied myself. I guess this could sure be interesting, I said to myself.

That was the first time I saw seen a group of strangers nude. Other than being naked in a locker room after gym classes or on intimate occasions with girlfriends, I hadn’t been exposed to nudity. That was plenty jolting all by itself, if disappointing, because most people were not nearly as good-looking naked as they were fancied up in their clothes. And I’d never been around old people who were naked. It was scary. Is that what happens to the body with age? Yikes. Look at those saggy old ball sacks. Is that what a mastectomy looks like?

That was my first thirty minutes in a personal-growth workshop. It only got wilder from there.

That night I learned that nearly everyone had signed up for this one workshop — and then would be returning home a week later with the intention of digesting what they had experienced and learned. That was the way people engaged personal growth workshops, one at a time with lots of time in between to make sense of the learning. I was completely ignorant about the depth and intensity of what we were about to encounter in others and ourselves. But I wasn’t going home after this workshop. I was about to immerse myself — again and again, from Sunday to Friday, Friday to Sunday, Sunday to Friday, Friday to Sunday — for the next five months, during which I would witness/experience heartbreaking loss, debilitating grief, painful sadness, mean-spirited hatred, terrifying fear, raw disgust, tantric sexuality, empathetic joy, and both the oddness and beauty of human individuality.

Encounter groups were not for the faint of heart. Group sessions would start after breakfast and often ran until midnight; on some days they’d keep going right through the night. They might last for days or even weeks or months. You could never be sure what good or bad news might surface and how it might resolve. And in the early years, many of them were done in the nude.

Over the next five months I learned that in this new world of psychology-meets-emotions-meets-the-body, we hold fears, we hold trauma, we put on façades, fake smiles, and stylish clothes as we all attempt to make the most of our lives — usually with mind, body, and feelings disconnected. The speculation was that this absence of alignment is at the source of much mental and even physical dis-ease. So, in encounter groups, with “Let’s get naked and express our real selves,” the idea was that the process could bring people to a point of openness from which they can discover their fears and learn to talk about feelings, hopes, and dreams that are deep and significant.

Everything about my first encounter group was otherworldly for me. As the days unfolded, some people cried about an illness they were grappling with, and others vented anger at an abusive parent or partner. Others shared their passions, some dealt with the sadness of losing a loved one. Everyone let down their guard, and we all grew closer, more open, more at ease with ourselves. It was touching and, in many ways, quite magical. We got to “see” everyone else and let them see us.

At the end of the first week, a few hours after saying goodbye to my newfound friends, I was joining another workshop with a whole new cast of characters, this one was titled Sensory Awakening. It was led by Bernard Gunther, who had just published Sense Relaxation: Below Your Mind. The theme of that group was learning to feel again in a hard-driving, highly uptight world. The first day, we each held a stone in our hand for many hours and then described the experience while the rest of us listened. Then we’d each wander off and find a flower, smell it, and study its petals. Later we were advised to sit quietly for hours and fully observe all the colors of the sunset and the sounds of the waves. On another day somebody would slowly bathe your feet in warm water, while across the lawn a flute played. To me there was nothing abusive, nothing sexual in this course. It was simply learning to feel the world with all our senses again. We also experimented with synesthesia — feeling sounds, tasting colors, smelling ideas. I thought, Wow, this is a different way to feel embodied. Other than exhilarating sexual sensations I had enjoyed from time to time, and the pain of breaking bones while playing sports, I’m not sure I had ever learned to feel with all my senses.

After a few hours soaking at the baths, taking in the ocean below the cliffs of Esalen, I got dressed and had some dinner, and then my next week’s class would begin.

My next workshop at Esalen was entitled The Passionate Mind, led by master yoga teacher Joel Kramer. Although I had already been practicing yoga for a year or so, Kramer’s approach was both athletic and supernatural — in an era when yoga hadn’t yet broken through into the mainstream. First, his asanas were propelled by his extraordinarily slow and deep breathing. He could do just about everything with his body I had ever seen in any yoga book. I was absolutely mesmerized. Second, he focused half the workshop on jnana yoga, which is the yoga of thought and problem solving. And third, he described and introduced us to the “edge” — that zone of expression/effort/resistance where most growth occurs. This became a core philosophy for how to engage change for me, which I’ll discuss further in later chapters. I came away from that group convinced that yoga wasn’t physical exercise but rather a path to a deeper mind and a more integrated self. Why hadn’t I been exposed to any of this in all my years of physical education in grammar school, high school, and college?

Then I joined another intense workshop: Gestalt Dream Analysis led by Dr. Jim Simkin. People had come here from all over the world to have every ingredient of their most troublesome or wondrous dreams — characters, colors, sequences, and outcomes — revealed as elements of their unconscious mind.

From that I rolled into a wild workshop focused on dealing with madness led by Esalen co-founder Dick Price. A brilliant, handsome, and charismatic Gestalt therapist and former mental patient at Agnews State Hospital, Dick had a level of grace, intensity, and insight I had never encountered before. These sessions were focused on the idea—recently proposed by R. D. Laing in The Divided Self — that all of us have regions of craziness and psychosis buried inside. Dick wanted us to think of the workshop room as a safe place to let these demons and angels out. I could write an entire book about that workshop alone.

The tendency toward nudity in certain workshops, while at first intimidating to me, also instigated some early moments of deep learning. Observing many people abreacting deeply held feelings, I was able to notice how emotions impacted physiognomy: how they breathed, how they held their shoulders, how they moved their hips and legs, how they gestured when emoting. Over the weeks and months, as I watched people with strikingly different backgrounds work through similar issues, it began to occur to me that there were patterns to how people embodied their minds. Had these sessions been dressed and in a therapist’s office, there wouldn’t have been much to notice. But in this nude Gestalt/encounter/psychodrama/yoga laboratory, I began to realize how feelings influence the flow of our energy, which influences our movements, which over time shapes the musculature, posture, and flow of our bodies.

Next was an entire weekend workshop conducted 100 percent in silence, which was a real bear for chatterbox me. Then another led by Dr. John Lilly on altered states of consciousness. Through intense breathing exercises, meditation walks, and other techniques, Lilly introduced us to his latest maps of human consciousness.

During these workshops, I wasn’t a spectator; I was a very active participant. I cried, I laughed, I convulsed, I let go, I regurgitated, I fought, I got made fun of, I discovered senses I hadn’t known existed, I felt feelings I didn’t know I had, I hallucinated, I portrayed people’s demons, I listened to people screaming about life’s unfairness, and I even let out a few primal screams myself.

I was amazed at how many people had been wounded or damaged in their lives; and how many were hoping that these new therapies might unburden them of their trauma. I was naïve, having enjoyed a youth and upbringing that was generally safe and secure. Witnessing firsthand the depth of other people’s suffering, how badly they had been bruised along the way, was jolting. I was shocked by stories of sexual molestation. I was saddened by folks who had lost a loved one to tragedy, illness, or mishap. And I ached when I learned about the suffering that so many people had lived through due to the dishonesty of people they had trusted. Notwithstanding co-founders Murphy and Price’s stated interest in exploring the frontiers of human potential, people were showing up at Esalen as if it was a modern-day Lourdes, hoping simply to be healed. Many were helped. Many weren’t. These months of “encounter” with folks of all ages and narratives exposed me to an interpersonal underworld that I hadn’t known existed.

My Esalen experience went beyond the workshops. I was also volunteering alongside community members in the organic vegetable garden, washing dishes while dancing to the Chambers Brothers, and taking nature hikes high in the mountains of Big Sur. With three or four different workshops going on each week, the lodge and campus were always populated by an interesting cast of characters — fellow seekers, numerous celebrities, and many potential playmates (remember, this was the free-love era). A great deal of cross-fertilization happened at the meals and also at the natural mineral baths. I loved to soak in the baths, particularly at night. As the stars rotated around the sky, I joined in some of the most interesting discussions I had ever heard — and did a lot of listening. I remember sitting in the baths one night while Princeton religious scholar Sam Keen was engaged in an intense discussion with Hector Prestera, a physician who dropped out to become an acupuncturist, and Dr. John Lilly, who had just done breakthrough research on dolphin brains and interspecies communications. They were discussing their views about whether the human mind could experience cosmic consciousness. It was eleven o’clock at night when the discussion began, and I sat there and listened to them explore one another’s views about this vast subject until the sun rose in the morning.

As I had more of these experiences with so many remarkable people, a narrative was emerging. It was the idealistic and hopeful notion that humanity might be at the brink of an extraordinary evolutionary jump, that we were going to see kinder people. We were going to have richer relationships. We were going to understand our bodies in a way that would help us be healthy and vibrant and orgasmic and beaming. We would see people less superficially and more deeply, and from all of that would come a new psychology, and new medicine, maybe even a new humanity.

Like an unfolding symphony, one workshop and discussion led to the next. As many parts of my body, mind, and spirit became activated, I thought this was what it must have been like in Paris after World War I, when great artists of the Lost Generation communed in cafés and salons. Maybe this was one of those moments when imaginative, well-intentioned people came together to think and talk and share and dream and ideate. Alongside that, I felt as though a somewhat different version of me was emerging. Who am I now? I wondered. What becomes of my former life? And what is my role in all of this?

Near the end of my five months of back-to-back workshops, one of my roommates at Esalen was a brilliant young man who was an undergraduate at Yale. He explained that he was getting independent-study credits for his week at Esalen. I wondered if I could do that retroactively at Lehigh. I wrote a letter to the deans, saying, “I’ve just finished a full semester at Esalen Institute, and I’d like for that to be considered as fully accredited education, as this is the cutting edge of psychology and medicine.” My psychology professors and department chairman all supported my request. And amazingly, the deans approved it, which allowed me to return to Lehigh, finish up a few assignments, and graduate along with my class.

While in that final semester at Lehigh, I applied to and was accepted into a special doctoral program at the Union Graduate School, part of the Union for Research and Experimentation in Higher Education — an innovative new consortium of more than thirty colleges and universities. This further distressed my parents, as they had hoped I was done with my “alternative” interests and would somehow find my way to either Harvard or Stanford. The Union Graduate School program allowed me to travel to different universities as well as nontraditional schools and centers around the world, including Esalen, to complete a doctorate on the “psychology of the body” — and I’d be the first person in the world to do so.

As part of my graduate program, I returned to Esalen and Big Sur for another two years of study and teaching — and thousands more hours of encounter, psychodrama, tai chi, Rolfing, bioenergetics, Reichian energetics, meditation, massage, shiatsu, the Feldenkrais method, Gestalt therapy, and a variety of yogic practices with prominent teachers such as Alan Watts, Joseph Campbell, Michael Murphy, Gregory Bateson, Baba Ram Dass, Joel Kramer, John Lilly, Bernard Gunther, Dick Price, Moshe Feldenkrais, Ida Rolf, and Chungliang “Al” Huang. I also continued learning from Jean Houston, Swami Vishnudevenanda, Carl Rogers, and others.

One of the first workshops I took when I returned was led by Hector Prestera and Will Schutz, who had been my first group leader back in 1970. I was fascinated by its title: Bodymind. In this workshop, which ran for seven days with ten to fifteen hours of therapy sessions per day, Schutz and Prestera combined encounter with psychodrama and Rolfing. Schutz, whose workshop I had been so impressed by two years earlier, was a psychotherapist, and Prestera was an internist, but they were both also recently trained as Rolf practitioners. This was one of the first times that two influential teachers from diverse backgrounds joined together to pool skills and talents regarding the bodymind in an experimental therapeutic setting.

What this meant for us as participants was that in addition to the usual encounter work, focused on interpersonal sharing and processing, we would explore the ways in which each of us animated our own body in relation to our unique characters and emotional histories. Right off the bat, Schutz asked our group, “Is anyone dealing with any recent loss or trauma?” A troubled-looking woman in her mid-forties raised her hand and explained that she was still struggling with the loss of her dad, who had died several years before. She missed him dearly, and because she was out of the country when he passed, she hadn’t gotten home in time for the funeral. Her sadness and guilt were entwined and were, in a sense, strangling her. Schutz said, “We’re going to stage a funeral right here, right now, if that’s okay with you.”

“Yes, it is,” she said.

“Who in this room would you pick to play your dad?” asked Schutz.

She pointed to a man in our group who in some way reminded her of her dad, and Schutz said, “Please ask him if he’d be willing to play this role, and if so, help him lie down like he’s in a casket. And who might be able to play your mom?”

She immediately turned to an older woman in the group and said, “You remind me a little of my mom.” Then she looked at me and said, “You can be my brother. He’s kind of an asshole, and he’s always trying to prove he’s better than me.” And to someone else, “Please be my cousin who is sweet and loving.”

And so, with specific direction from the woman and the group leaders, we all proceeded to act our parts. What ensued was powerful. Holding her deceased dad in her arms, she told him all the things she had wanted to tell him, and she began crying when she shared how much she had always loved him. Although she had been very buttoned up when she started, when she professed how much she missed him her chest began to heave, and she began sobbing profusely. Then, all of a sudden, other people in the room started sobbing. I guess that inside all of us there’s a well of sadness over the death of a loved one. We were using improvisational drama to go beyond words and activate a wide range of feelings. And since most participants were nude, it was quite a lot to take in. Through this facilitated psychodrama, nearly everyone let go of some sadness and we all wound up feeling both lighter and closer. By the time everyone had commented on their experience, it was after midnight. We all hugged, said good night, and went off to our rooms and cabins to sleep.

The next morning, twelve of us found ourselves sitting in a circle around one of the group members who was being Rolfed slowly and simultaneously by both Schultz and Prestera. This middle-aged, fit-looking man encouraged to let go and express himself and his emotions in any way he wanted during the Rolfing. Because the massage work is deep, the Rolfee may experience pain. As Prestera’s and Schutz’s hands moved over and into his body, he responded with some defiant screams, sobs, and even laughter, as feelings and memories seemed to be coming up from nowhere. But they weren’t coming from nowhere — they had been trapped in his body. I had absolutely never seen anything like this before.

As the days passed and our stories emerged, we began to feel one another’s pains and pleasures with a great deal of openness and sensitivity. Since we were all completely naked throughout the group sessions, there was nothing covered up. It was especially interesting to me to note how each of us responded to certain aspects of another’s ordeal. It reminded me of the first time I learned to tune a guitar. I was amazed to find that when I struck a particular note on one string, if there was another guitar in the vicinity, the same note on that guitar would vibrate too, even though I hadn’t touched it. In very much the same way, it seemed to me that each of us was tuned to a variety of notes and chords (feelings and attitudes), and when these vibrations were struck in our presence, we resonated.

Each day three more of us were Rolfed as part of the group ritual, and each day I watched as different group members responded to the process in a unique fashion. Since the number one Rolfing session — the one being practiced in our workshop — was a standard procedure, most variation in response was due, it seemed, to the physical or mental state of the individual being Rolfed rather than to variations in pressure or movement on the part of the Rolfer. My observations now went far beyond what I had noticed back in 1970. I began to see that similar stories were being recalled and abreacted by different members of the group. What was even stranger: these similar stories came up when the sameparts of different Rolfees’ bodies were confronted. For example, feelings and memories of being left and neglected repeatedly appeared when a Rolfee’s chest was being released. When the upper back was worked on, the muscular confrontation was repeatedly accompanied by strong feelings of rage and anger. Rolfed jaws released sadness; Rolfed hips released sexuality; Rolfed shoulders seemed invariably to tell stories of burdens and stressful responsibilities. The crazy idea came to me that the body was like a multidimensional circuit board: when certain switches were triggered, similar stories and experiences emerged from the same body parts belonging to different people.

At first this didn’t seem possible. I was having a hard time buying the notion that emotions were somehow stored in the body and that there were general patterns by which they stored themselves. Yet as each day passed and I watched more deep emotions released and worked through, this possibility seemed less unreasonable. I became fascinated by the body as a storehouse for feelings and memories.

While studying everything from yoga to tai chi to dream analysis with Esalen leaders, I chose to apprentice myself to Schultz, who agreed to serve on my graduate committee, and Prestera, who was writing The Body Reveals and agreed to become a mentor to me. I was in encounter group therapy for more than one thousand intense hours. This allowed me to observe hundreds of bodies in the process of interacting and emoting in a manner that no traditional psychotherapist could have witnessed. As before, I wasn’t a bystander — that would not have been tolerated. Encounter, Gestalt, psychodrama, and other therapies were inclusive, confrontative, and intense. I was fully engaged and involved. Sometimes it was exhilarating, and other times it was really rough. Week after week, I’d be sitting in the group meeting rooms watching people deal with psychological and emotional issues, and I couldn’t help noticing what was happening in their bodies.

In out-of-session discussions with group leaders, it was mentioned that when Freud was doing his pioneering work, his patients would be fully clothed, and they would lie down on his couch and talk about their feelings. This was an utterly different laboratory for observing the mind and body at work. We realized that the odd combination of New Age interests, Big Sur’s isolation and natural setting, the coming together of countless different therapies and research modalities, and a post-Woodstock acceptance of casual nudity gave us a theater to observe people’s body-mind patterns in unprecedented ways. And I was right in the middle of it all.

I became fascinated by the work of Dr. Wilhelm Reich, a student of Sigmund Freud who developed theories about what he called body armor. He believed that when people go through a trauma or difficult experience in their lives, they take it in, and related parts of their body react in terms of either ease and flow or conflict and tension. Depending on the intensity and/or frequency of the experience, these tensions can become chronic and turn into a kind of protective body armor. Reich postulated that throughout our lives, our bodies develop various pieces of armor plating, which both protect us and lock feelings in, while also keeping many feelings out. Depending on the nature of the experience, the armor might be in the thigh or it might be in the groin. Maybe in the chest. Or the shoulders and back. Just as a young tree may twist and grow around the rock it is embedded in, our bodies twist and grow around the emotionally driven holdings in our body. Looking at all these twisted humans, I found it made sense. Further, Reich believed that when energy gets blocked somewhere, it becomes like a dammed river. If you block a flowing stream, the water is going to get stuck, stop flowing. If a child growing up has a need to cry, the crying expression might begin in the gut, then move up through the chest, then flow through the throat, and show up as a quivering in the jaw, before releasing from the mouth and face. If the child is told, “Don’t cry,” the crying process gets stuck. The next time the child is told not to cry it might get locked again. The time after that, it might get locked and stop altogether. By the time the child is seven or eight, crying doesn’t come easily. Instead, the energy and the experience unconsciously become locked in his jaw, throat, chest, or stomach — depending on where it’s been getting cut off.

As an adult, if this person feels a need to cry, instead of the emotion naturally flowing out, the individual will just tighten his gut or squeeze his jaw or whatever. Usually, this tightening moves out of his conscious experience. I observed this in both bioenergetics and Rolfing, when people’s jaws were released and rivers of tears came crying out. Imagine that a person is angry and feels the rage flowing up into her arms and then it’s stopped. Or what if someone is feeling like he wants to run away and instead he freezes up? Or how about someone who wants to express love but is denied? These feelings don’t necessarily just evaporate. I wondered if they became embodied. I wasn’t alone in this enquiry. These kinds of questions were being asked by doctors and psychologists around the world — and they were seeping into popular culture.

During those years, the workshop rooms became living laboratories for me, in which I would watch the bodymind in action. With a passion that verged on fanaticism, I made mental notes to myself about what sorts of people were shaped in what ways. Conversely, I would look at the physical makeup of those who were in a Gestalt session or were being Rolfed and try to imagine the sort of memories and blocks that would be released by the therapeutic intervention. I was often spot-on. Just as the mind reflected the body, the body reflected the mind—if you could decipher its language. As the months passed, my feelings and observations were leading me to develop a psychosomatic system that accounted for the direct relationships between particular feelings and beliefs and the shape, energetics, and flow of particular body parts and regions. Was I too young to be trying to make sense of all this? Yes. In fact, at twenty-two, I was almost always the youngest person in the workshops, without enough training or education to comprehend much of anything I was seeing. Then again, I didn’t have any medical training or background as a psychotherapist to get in the way of observing what was manifesting. My youth, ignorance, and inexperience may have worked a bit to my advantage, as I didn’t have an entire body of perspective to set aside.

Making this the thrust of my doctoral studies, I compiled insights from Lowen’s writing and overlaid it with Reich’s and then integrated ideas from Perls and Schutz. A pattern of relationships between our minds and our bodies emerged. For example, the left side of the body — corresponding to the right side of the brain — was more involved in the feminine aspects of one’s self, while the right side of the body was more driven by the masculine forces. The top half of the body seemed to be oriented toward socializing, outward expression, and manipulation, while the bottom half was more oriented toward privacy, grounding, stability, and support. The feet and even the shape of the arches reflected how one grounded oneself emotionally, while the thighs often reflected personal will or strength. The way the pelvis was tipped — downward or upward — often correlated with how one activated or blocked sexuality, while the abdominal regional was the storehouse for deep feelings. And on and on. By studying everything I could get my hands on, I began to craft a master map of the bodymind.

Then my studies and investigation were impacted by an entirely other universe of views. Someone offhandedly gave me a copy of The Serpent Power, by Sir John Woodroffe, in which he explained the realm of kundalini yoga. Although I had been diligently practicing hatha yoga for several years, the kundalini perspective on how the mind is embodied was new to me. The central idea of kundalini yoga is that within the spine, in a hollow region called the canalis centralis, is an energy conduit the Hindus called sushumna. Along this conduit, from the base of the anus to the top of the head, flows the most powerful of all psychic energies, kundalini. On either side of this canal are two additional energy channels. One is called the ida, which originates on the right side of the spine, and the other is the pingala, which begins on the left. These two currents are believed to correspond to the male and female life forces said to coil upward around the spine like snakes, crisscrossing at seven vortexes, called chakras or energy wheels. I devoured Woodroffe’s book as well as every other book about this subject I could get my hands on, from Gopi Krishna’s Kundalini: The Evolutionary Energy in Man to Carl Jung’s Psychology of Kundalini Yoga. Apparently, long before the Reichians and Rolfers, and before Maslow had imagined his “hierarchy of needs,” within ancient Hindu literature existed a model of the body, mind, and spirit in which each chakra was concerned with very specific aspects of human behavior and development.

In addition, there seemed to be a progression in the ascending locations of these chakras, sort of like Maslow’s hierarchy, but grander. Armed with these new ideas, I intensified my yoga practice to around four hours a day as I tried to personally “feel” each of the chakras and the behavioral neighborhoods that lived within my own body. As I moved very, very slowly through my extensive set of asanas each day and paid careful attention to how my mind shifted in relation to each region, I was consciously exploring my own inner stories.

Like a jigsaw puzzle coming together, when I overlaid the Kundalini model with that of Reich, Lowen, Schutz, and Perls, what did I find? They matched!

Then, at the ripe age of twenty-three, while sitting under the stars in Big Sur, I decided to try to write a book about this new model of mental and physical health and personal growth. My intent was to distill these converging understandings into a common framework with a common language.

In 1974, I had been living in Big Sur for several years while working on my doctorate in psychology and writing Bodymind. I had a little cabin 30 miles north of Esalen that I rented for $150 a month, which I could barely afford by teaching workshops at Esalen and other growth centers. It was a dump, but I loved it. It was nestled in a redwood grove right alongside the Big Sur River. Since I had read Siddhartha several times by then, and like many of my peers was hoping to become enlightened as soon as possible, living next to a flowing river seemed a perfect fit. My place was located about an hour south of Monterey, right before you got to the Big Sur post office. To get to it, you had to cross a tiny bridge on the west side of Highway 1, secured by a locked gate. Once you crossed the bridge, the dirt road opened onto miles of protected forest, streams, and hiking paths. Although mine was a beat-up little house, the setting was spectacular, and the property private, secure, and cozy. I dreamed I would stay there for years, maybe forever.

There were no cell phones of course, and there was no television reception in Big Sur. The only radio access we received was late at night: Wolfman Jack beaming out of LA. Because there was almost no technology in that era, I filled up my time with learning, reading, writing, playing music with friends, meditating, thinking, daydreaming, hiking, doing yoga, having fun, and enjoying the free-spirited sexuality of the era. This was a window in time, after the introduction of birth control pills but pre-AIDS, when “Make love, not war” was more than a slogan — it was a lifestyle. It was a beautiful and crazy era, and I loved my life in Big Sur.

I drove the half hour to Esalen almost every day, training there with various leaders, teachers, and authors in the fields of psychology, yoga, bioenergetics, psychodrama, sensory awareness, meditation, and tai chi. I was also co-leading workshops, and my youth made me somewhat of a novelty. At night I returned to my cabin in the woods, which I rented from a guy named Jan Brewer, who owned a number of properties in the area. I had never met him, as he was believed to be living in New Zealand. I simply sent my monthly rent checks to the post office box of his property manager. Word was that Brewer was quite an odd character: movie-star handsome, certifiably crazy, and considered a violent outlaw by anyone who knew him. Back in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s Big Sur was a wild “multicultural” mosaic. You had the bikers (principally Hells Angels), gypsy-style wanderers, hippies, and movie stars hiding out, and many outlaws—ex-cons, lawbreakers, and renegades of every sort. And of course, the Esalen community within Big Sur was populated by professors, revolutionaries, and belly dancers. It was a strange universe of artists, seekers, and crazies. For me, after a straitlaced upbringing in urban New Jersey, it was a psychedelic fairy tale. Every night as I watched the stars, I thought, “Why would I ever want to leave here?”

Then one day, at around five thirty in the morning, bang! bang! bang! I shot up from a deep sleep on my mattress on the floor and trudged naked to the front door. Standing in front of me was a guy with a very bad mood written on his face. He resembled a young Clint Eastwood, if you imagine Clint Eastwood having dropped a very toxic tab of acid. I was thinking, Who is this guy and how did he get through the gate and onto my property?

He barked, “Hey, are you living here?” It seemed like a rather dumb question, but I didn’t think it wise to point that out.

“Yeah,” I said. “I am. What do you want?”

“Get out,” he barked, then raised his voice and declared, “I’m Jan Brewer. I own this property, and I want you out now!”

I said, “You’ve got to be kidding me. I like living here and I have another year on my lease.”

Brewer reached under his vest and produced a gun from the holster hidden beneath, which he pointed at my head. He said, “You're leaving.”

I asked, “At the end of my lease?”

“No, now.”

I looked into his eyes and realized he was not fooling around. Then I looked at his gun and said, “Okay. I guess I’m leaving right about now.”

Moving his gun closer to my face, he said, “You have until sunrise.”

During the next hour, in a panic, I loaded my clothes, typewriter, diary, and guitar into my van. By the time the sun came up, I no longer had a place to live. I had lived in my van before — during the time I had spent wandering across America — and figured I could live in it again. Over the next months I tried with no luck to find another place to rent in Big Sur. I considered moving back to New Jersey or Pennsylvania, or maybe Colorado or Florida. I crashed at Big Sur friends’ homes and campsites for a while, but things just didn’t feel right. In truth, I was rattled.

I asked some friends for advice, including the remarkable Dr. Jean Houston, who was on my graduate committee and became a very influential person in my life. Jean was — and still is — a brilliant philosopher, author, teacher, and storyteller. In many ways she’s bigger than life.

Jean said to me, “Kenny,” she always called me Kenny, “It’s time for you to leave Big Sur. Your time is up. You’ve got the training. You’ve got the skills. Now it’s time to do something big with all of that!” What I had been building was a sort of fluency in all the newly popular therapies and a few ancient ones as well. I could teach yoga. I could lead encounter groups. I could conduct Gestalt and psychodrama sessions. I could do these so-called alternative therapies, and I somewhat understood them. Jean was a selfless connector — one of those grand human beings who bring people together — just because she loved doing so. I used to wonder if she wasn’t a gift to our world from some advanced race of beings. She said, “You need to meet my best friend, Gay Luce, who recently moved from the East Coast to Berkeley.”

“Okay, why?” I asked.

“Well,” she said, “Gay wants to start the most amazing human potential project that has ever been created, and you should be working with her and her collaborator, Eugenia Gerrard.”

I drove up to Berkeley to meet Gay Gaer Luce, who lived in the Berkeley Hills. She was twenty years older than me. She had been a well-respected researcher, psychologist and writer at the National Institutes of Health and had dropped out to move to the San Francisco Bay Area, where she believed the future was unfolding. She had written several books; one, titled Body Time, about biologic rhythms, had really caught my attention.

I met with Gay and her collaborator, Eugenia Gerrard, who was in her mid-thirties and was trained as a family therapist. She too was a spectacular human being. They explained their dream that, rather than these weekend personal-growth workshops or evening lectures focused on one thing or another, this was going to be an all-in, comprehensive, yearlong self-actualization curriculum with a pilot group of participants who would meet for a half day each week and also have one to two hours per day of personal practice assignments.

I was young, jobless, and homeless, and this all seemed totally exciting to me. I thought, Well, here we are at the beginning of 1974 and Berkeley’s kind of cool. It’s not Big Sur, but it sure isn’t Newark either. So I told them to count me in.

Gay knew a lot about mind-body types of psychotherapy, and I was going to contribute yoga, Gestalt, and psychodrama. Eugenia had a deep interest in co-counseling and using breathing techniques for stress management and healing. In addition to ourselves, since Northern California was brimming with consciousness types of every stripe, we imagined we could invite many renowned teachers, from Erik Erikson (adult development) and Ken Pelletier, the young psychologist and medical student who was writing the pivotal book Mind as Healer, Mind as Slayer to Robert Monroe (out-of-the body astral traveling) to Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (death and dying), to provide special sessions. We were surely naïve, idealistic, and enthusiastic at that moment, but we imagined that we could weave together both ancient and new therapies, techniques, and experiences, and put a group of people through it for an entire year — at the end of which they’d be, you know, next level.

Gay was friends with Stewart Brand, who lived across the bay and had just conceived and published a radical retailing/consciousness idea he called the Whole Earth Catalog. Stewart was so intrigued by what we were trying to do that he provided our group with five thousand dollars so that we could file as a not-for-profit.

As we were filling out paperwork for our project, we realized we needed a name. What were we going to call ourselves? The Human Potential School? The Mind-Body Collective? Consciousness University? We were trying out all these hokey names, and someone — I think it was Gay — said, “What about using the word “holistic”? None of us had ever heard that word. She explained that there had been a South African philosopher named Jan Smuts who had used the word maybe fifty years earlier. Okay, holistic what? “How about ‘holistic health,’ and we can be a ‘council’ — building off the American Indian idea of a group of leaders?” We loved it. But how do we spell it? I thought it should be spelled w-h-o-l-i-s-t-i-c, because we were bringing different ideas together into a whole. Gay, who at the time was a board member of the Nyingma Institute, a Tibetan Buddhist center in Berkeley, preferred that it be based on ‘hol’ as in “holy-istic.” We ultimately landed on Holistic Health Council (as you know – the concept spread).

Then, boom, Gay’s mom, Fay Gaer, an absolutely lovely and kindhearted seventy-five-year-old, suffered hypertension that was making her woozy. Frustrated with traditional Western medicine, Gay started doing biofeedback and breathing therapies with her mom, and she swiftly got better. So out of left field, Gay said, “Let’s fill our human potential school with old people!”

I responded, “Old people? What are you talking about?”

Gay went on. “Let’s try biofeedback, tai chi, yoga, meditation, psychodrama, art therapy, and journal writing. Let’s see if we can use these techniques to help older men and women feel more alive than they have felt for years! Who knows, maybe we’ll create a revolution in the way the world thinks about aging — and possibly transform medicine too. And let’s change our name from the Holistic Health Council to the SAGE Project.”

I thought, That’s a weird idea. How do I feel about old people? I like my grandparents a lot. I don’t have a problem with old people. They’re all right, but they’re definitely not as appealing to me as young people. Do I really want to base my career on old people and aging? I don’t think so. So I said to Gay, “I’ll tell you what. I’m going to help you and Eugenia set up the program blueprint — that will be both challenging and interesting. It should take a few months. But then I’m out of here.”

We put the word out, and a diverse group of elderly people started signing up. Our pilot group had twelve participants, and the first year we conducted all our meetings in the living room of Gay’s house in the Berkeley Hills. Before I knew what hit me, I was sitting on a pillow in a circle, not with good-looking, playful hippie chicks or dudes, but with grandmas and grandpas with arthritis, canes, ostomy bags, and cancerous skin.

Then everything changed for me when they began sharing their stories, hopes, and fears. At that point in my life — like so many others — I was searching not only for transformative therapies and practices, but for wise guru types. Not that I necessarily wanted to follow one. I thought of myself as a student in search of greater awareness. And I assumed the keepers of these insights would be famous professors, experts, authors, or swamis of one sort or another. It had not occurred to me that regular, everyday older people could in fact be the true holders of wisdom.

I didn’t leave the SAGE Project after a few months. In fact, I had the honor of working for the next five years with Gay and Eugenia as our idealistic little project expanded in scope and number of participants, received funding from the NIMH, and became the model for hundreds of courses, programs, clinics, and schools worldwide. All of this while the holistic health field rose up like a volcano from the multidisciplinary study group in Gay’s living room.

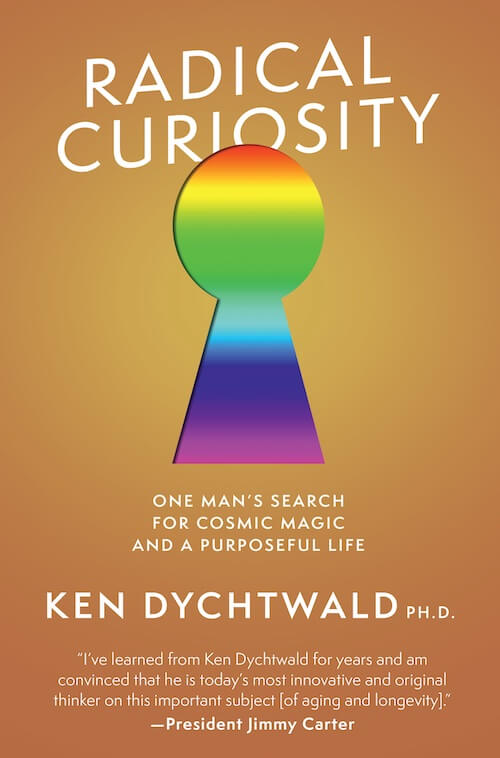

Who would have imagined that my Esalen experience and then my involvement with the SAGE Project would launch me into a 40+ year adventure in the field of gerontology? This has included presentations to more than two million people worldwide, meetings with numerous presidents and world leaders, learning from many extraordinary teachers such as Bucky Fuller, Michael Murphy, Maggie Kuhn, Huston Smith, Betty Friedan, and Jimmy Carter, and writing 17 more books after Bodymind. And overall, a life which, driven by curiosity and a desire for cosmic magic and purpose, has had its twists and turns, ups and downs, but from which I have learned many profound life lessons about love, family, money, work, risk-taking, success, aging, and death (as the rest of this book will reveal).

Thank you, Michael Murphy, for birthing the Esalen Institute and I guess I owe some thanks to Jan Brewer, for kicking me out of my house and opening the path to my destiny.

Life can only be understood backward. But it must be lived forward. — Søren Kierkegaard

“Remembering to be as self compassionate as I can and praying to the divine that we're all a part of.”

–Aaron

“Prayer, reading, meditation, walking.”

–Karen

“Erratically — which is an ongoing stream of practice to find peace.”

–Charles

“Try on a daily basis to be kind to myself and to realize that making mistakes is a part of the human condition. Learning from our mistakes is a journey. But it starts with compassion and caring. First for oneself.”

–Steve

“Physically: aerobic exercise, volleyball, ice hockey, cycling, sailing. Emotionally: unfortunately I have to work to ‘not care’ about people or situations which may end painfully. Along the lines of ‘attachment is the source of suffering’, so best to avoid it or limit its scope. Sad though because it could also be the source of great joy. Is it worth the risk?“

–Rainer

“It's time for my heart to be nurtured on one level yet contained on another. To go easy on me and to allow my feelings to be validated, not judged harshly. On the other hand, to let the heart rule with equanimity and not lead the mind and body around like a master.”

–Suzanne

“I spend time thinking of everything I am grateful for, and I try to develop my ability to express compassion for myself and others without reservation. I take time to do the things I need to do to keep myself healthy and happy. This includes taking experiential workshops, fostering relationships, and participating within groups which have a similar interest to become a more compassionate and fulfilled being.“

–Peter

“Self-forgiveness for my own judgments. And oh yeah, coming to Esalen.”

–David B.

“Hmm, this is a tough one! I guess I take care of my heart through fostering relationships with people I feel connected to. Spending quality time with them (whether we're on the phone, through messages/letters, on Zoom, or in-person). Being there for them, listening to them, sharing what's going on with me, my struggles and my successes... like we do in the Esalen weekly Friends of Esalen Zoom sessions!”

–Lori

“I remind myself in many ways of the fact that " Love is all there is!" LOVE is the prize and this one precious life is the stage we get to learn our lessons. I get out into nature, hike, camp, river kayak, fly fish, garden, I create, I dance (not enough!), and I remain grateful for each day, each breath, each moment. Being in the moment, awake, and remembering the gift of life and my feeling of gratitude for all of creation.”

–Steven

“My physical heart by limiting stress and eating a heart-healthy diet. My emotional heart by staying in love with the world and by knowing that all disappointment and loss will pass.“

–David Z.

Today, September 29, is World Heart Day. Strike up a conversation with your own heart and as you feel comfortable, encourage others to do the same. As part of our own transformations and self-care, we sometimes ask for others to illuminate and enliven our hearts or speak our love language.

What if we could do this for ourselves too, even if just for today… or to start a heart practice, forever?

Be yourself; everyone else is already taken. — Oscar Wilde

I grew up in the 1950s and ’60s in a hardworking, middle-class community in Newark, New Jersey. During my first five years of life, we shared a duplex with my grandparents, my mom’s parents. Then, thanks to a GI home loan, my dad moved us to a four-bedroom house in the Weequahic section of Newark, one block away from our grammar school and three blocks from the high school. We had a driveway and a backyard with enough space for a basketball hoop on the garage. My brother and I were in heaven. We had one black-and-white television set with four working channels. Most Sunday nights we’d pile into our family car to drive to Uncle Marty and Aunt Ethel’s house to watch The Ed Sullivan Show in color. We had two telephones: one was downstairs on the wall in the kitchen, and the other was upstairs in my parents’ room. My parents shared a car, and my brother and I had bicycles, which was how we got everywhere we wanted to go. We didn’t have much, but neither did anyone else.I had a great crew of friends, and everyday — rain or shine — we played in the streets or in the playground after school.

Everyone was trying to make something of themselves. My father was a fiercely hardworking guy who wanted to be successful. For him, work wasn’t about “finding his bliss,” it was about being a responsible husband and father. His dad had skipped out on him, his brothers, sister, and mother for almost ten years during the Depression. In contrast, my dad wished to be a reliable family man. He wanted our family to be living the American dream. Neither of my parents had gone to college, but neither did the parents of most of my friends.There wasn’t a need or desire for excess; if anyone had it, we certainly weren’t exposed to it. The kids on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand coming out of Philly looked and acted a lot like my friends, who were a cross between the characters in Grease and Diner.

As a teenager,I was a normal, reasonably well-adjusted kid and a conscientious student, getting all As throughout high school. I was also a pretty good athlete. I was captain of the tennis team, and my friends and I played a lot of basketball. Our Jewish Community Center (JCC) basketball team — comprised of many of my best buddies — won the state tournament, then the regional, then we took first place in the national championship. Competitive team sports were, without a doubt, the master narrative and favorite part of my growing-up years.

The rules of life were simple, almost two-dimensional. There wasn’t any talk about personal feelings or identity, self-actualization, discovering your passion, or mental health. I didn’t do much deep thinking about anything. No one I knew did. The most famous person from our neighborhood, Philip Roth, was a decade or two older than me. When he first achieved fame as a writer and storyteller, it was with a book about a guy who masturbated all the time. I didn’t have much perspective or insight about my life’s path. I figured I’d go and get a degree, start a career as an electrical engineer or physicist, fall in love, get married, have children, and live in a house within a few minutes of where my mom and dad lived. So I went to a fine engineering school at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. I partly went because they accepted me on early notice, and it was a good school, and also because I could be on a bus to get home for a visit in around two hours. During my first two years, I jumped wholehog into science. In truth, I didn’t enjoy it very much. I didn’t particularly like the classes, the homework, or the professors. Living in a dorm and then in a frat house — on an all-male campus with our sister school, Cedar Crest, a half hour away — we had a truly stilted social life. In the larger world, the sexual revolution was awakening and protests to the Vietnam War were erupting everywhere. I got drunk on most weekends and tried pot, but my state of mind remained relatively plain vanilla and middle of the road. Overall, my grades were fine, and I was making progress toward adulthood, albeit feeling somewhat uninspired.

In my junior year, I had to take some electives. My curriculum advisor suggested I take a social science course to round out my engineering and physics training, so I wandered into a psychology course being taught by a cool young professor (every campus had one). It was 1969,and I honestly didn’t even know what psychology was. The professor, Dr. Bill Newman, had recently graduated with his PhD from Stanford, so he’d been living in the San Francisco Bay Area. At that time, before the Palo Alto peninsula became Silicon Valley, it was the home of Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, Jerry Garcia, and a whole new drug-fueled bohemian culture. Dr. Newman was smart, fun and hip, very unlike my physics and chemistry professors, who were quite square. The course was titled “The Psychology of Human Potential,” and from the first lecture, it absolutely blew my mind. It was based on the idea that human beings have extraordinary capabilities — vast mental, physical, and even spiritual potential — and that we were only tapping into maybe five percent of it. There was also the suggestion that our modern educational and physical training programs were quite pedantic and designed to activate only a tiny portion of our capabilities. This point of view completely turned me on and excited my imagination more than anything I had ever encountered. It occurred to me that there was a multicolored worldout there, yet I was trapped in the black-and-white anteroom. The first textbook of the course was The Varieties of Psychedelic Experience by psychologists Robert Masters and Jean Houston, and the second was Psychotherapy East and West by philosopher Alan Watts. The third was Toward a Psychology of Being by breakthrough “self-actualization” thinker Abraham Maslow, and the fourth was a book by Dr. William Schutz called Joy, about the exaltation one feels when one breaks free of restrictive and confining patterns. All these books were recently written, filled with big ideas, and, for me, mind-blowing.

As I dug deeper and deeper, I learned that there were ancient therapies and practices such as meditation, tai chi, and yoga that could unleash these potentials. I learned about many emerging new approaches, including bioenergetics, Rolfing, encounter groups, and Gestalt therapy, that were designed to loosen mental and physical constraints and liberate people to live a bigger, grander version of their possibilities. I immediately started practicing beginner’s yoga and meditating. I also gathered some of my electrical engineering friends to build simple biofeedback equipment with which we attempted to alter our brain waves while in sensory-deprivation chambers. I went to the library and started gorging on everything I could find that probed the search for human potential: Ram Dass’s Be Here Now (a Xeroxed copy of the manuscript), P. D. Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous, Alexander Lowen’s The Betrayal of the Body, and Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha, to name a few. Over my life, I have heard people tell stories of their awakening sexuality, or their discovery of their personal passion for playing the piano, or even their realization of God. For me, this was like my previously dormant volcano of curiosity had exploded. Who am I? How does my mind impact my body? Do I have any superpowers? If so, what are they? Does my brain contain all of my mind? Is there a God, and if so, what’s his or her plan? Am I reincarnated, and if I am, what other lives have I lived? Are humans done evolving? Evolving to what? What is my purpose? Do I have a destiny? Questions poured forth unrelentingly. I had never really experienced angst before, but I was swimming up to my eyeballs in it now. I knew I had to find answers.

I couldn’t help but notice that in the human potential authors’ bios, the name Esalen came up time and again: Alan Watts is a teacher at the Esalen Institute or William Schutz left Harvard to be a teacher at the Esalen Institute, or Fritz Perls teaches workshops at the Esalen Institute. The pursuit of human potential became my singular focus, and I knew I couldn’t get enough of the real deal in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. I abruptly decided to drop out of Lehigh and go to the source of this revolution — California, specifically, the Esalen Institute perched atop the mysterious cliffs of Big Sur. This decision surely didn’t make my mom and dad happy. They thought my mind had become unhinged and they were losing their fair-haired, all-American boy.

I sold everything I had and cut into my bar mitzvah money and the meager savings I had accumulated from my summer jobs to pay for the workshops I was going to take at Esalen. I imagined that five months at Esalen would be kind of like a semester at college. So, very innocently, I signed up for five months of nonstop workshops.

When the day arrived for me to fly west, I said goodbye to my family. My brother, Alan, who was three years older than me and a straight arrow, was bewildered by the whole thing. My mom was, as was her nature, encouraging but nervous. When my dad said goodbye, he broke down and sobbed — something I had never seen him do before.

I took off from Newark Airport, bound for San Francisco. I had never been farther west than Pennsylvania. Upon landing, I had only to begin walking through the terminal to be immediately entranced by the Summer of Love look, style, and attitude that made California feel so completely different from New Jersey. There were so many young people, and they were so attractive, so seductive.

Esalen had a van that picked me up in San Francisco for the drive to Big Sur. Inside were two women and an older man, both heading to their first Esalen experience. Soon enough, my new friends and I were on the way through the gorgeous terrain. I kept the window open so I could feel the cool ocean air. It was a ride unlike any I had ever taken. As we passed Monterey Bay heading south, an unending cascade of massive mountains rose up to my left, while the highway began to lift me above sea level on the precarious edge of a winding cliff to my right that plummeted to craggy rocks and the tempestuous Pacific Ocean below. Having grown up near the Atlantic, with its flat beaches and pulsing shoreline waves, I could not believe the primitive strength and rugged beauty of the Big Sur Pacific coastline.

For the next hour, there were countless hairpin turns, each one revealing a panorama of the Santa Lucia Mountains meeting coastline more incredible than the one before. All along the route we spotted tourists who had precariously parked their cars on the narrow shoulder to snap a few breathtaking photos, and hippie boys and girls thumbing their way to who knows where. Out at sea, we caught glimpses of whales breaching. At one point the van driver whispered over his shoulder to his spellbound passengers, “This is why it’s called God’s country.”

And then, about fifty winding miles south of Monterey, on the ocean side of the road, a modest wood sign, which still exists today, declared ESALEN INSTITUTE / BY RESERVATION ONLY.

We had arrived. I had arrived.

The van pulled down the steep driveway to reveal an Eden-like campus with a sumptuous vegetable garden unlike anything I had ever seen. I might as well have just landed on an alien planet. We jumped out to register in the Esalen office, staffed by beautiful hippie women and men. Around the fourteen-acre property, gorgeous rock formations were swarmed by flowers, a great hall served as a communal dining room, a spectacular canyon with waterfalls contorted among cypress trees, and, of course, a natural hot spring was filled to the brim with naked folks laughing, playing, or staring out across the ocean.

(Fast-forward many years: in 2015 my wife Maddy and I are watching one of our favorite TV shows when its protagonist arrives on Esalen’s mysterious cliffs, seeking answers to his own inner turmoil and to his curiosity about where pop culture is heading. Turns out that the last episode of Mad Men sends Don Draper to Esalen, an end point that is actually a beginning. Draper’s arrival takes place in exactly the same year and season when I was first there — although I don’t recall meeting him at the time!)

That first day, I found my way to my shared room and unpacked. I ate alone in the cafeteria-style dining hall, mesmerized by the truly amazing sunset over the Pacific. Soon after, I walked up the hill to a funky building where I’d be joining my first workshop. It was an “encounter group” led by the renowned Dr. William Schutz, the Harvard professor who had dropped out of academics and invented encounter groups. Schutz had gravitas at Esalen. He had recently published his controversial book Joy, and with the popularity of the 1969 movie Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, which playfully spoofed one of his Esalen workshops, Will Schutz appeared on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson many times demonstrating trust exercises with other guests and declaring the need for everyone to get open and honest and tell the truth about what they were feeling. During this anti-establishment period — fueled on the one hand by antiauthoritarian political protests and on the other by the sensuality and freedoms being espoused by a new era of sex, drugs, rock and roll, and mind expansion — Schutz and many others felt it was a time for a new psychology.

In addition to having taught traditional psychology at Harvard, Schutz had recently trained with Ida Rolf to become a Rolfer. Because he and Fritz Perls both lived and taught at Esalen, Schutz picked up many of Perls’ Gestalt therapy insights and techniques. He was also fascinated by the work of Wilhelm Reich, Moshe Feldenkrais, and J. L. Moreno — and he combined all those different modalities into a new kind of therapeutic dynamic, which he called an “encounter group.” Depending on how you looked at his approach, it was either a brilliant synthesis of numerous mind-body therapies or a zany, touchy-feely mash-up — or possibly both.

The encounter group movement aimed to achieve personal openness, honesty, and realness by stripping away the façades, unpeeling the armor, and uncoiling the usual defenses. No need for pretense or cover-ups: if you’re hurting, be hurting. If you’re angry, be angry. If you’re deeply sad, let it out. If you’re jealous, talk about it. Before then, most psychotherapy was done one-on-one for an hour or so in the privacy of a therapist’s office. And it could take years for a breakthrough to happen.