In the fall of 1962, Jim Fadiman became one of Esalen’s first workshop leaders with his course “The Expanding Vision,” co-taught with Willis Harmon. Fadiman has had a lifelong association with the institute ever since. World-renowned for his research on microdosing psychedelics, he has appeared in countless films as a leading authority on the subject, including Science and Sacraments (2013) and Inside LSD. (2009). His books include The Psychedelic Explorer's Guide: Safe, Therapeutic, and Sacred Journeys, Be Love Now, Essential Sufism, and The Other Side of Haight.

I graduated from Harvard in 1960. I was boringly straight, repressed, and sarcastic, not untypical of a Harvard student. I was also the teacher's pet of a professor named Richard Alpert. During the summer of 1961, I was living in Paris, writing a remarkably bad novel, and Richard passed through on his way to Copenhagen, where he, Timothy Leary, and Aldous Huxley were presenting the Harvard psilocybin research up to that point.

We spent an evening together, and he was just in wonderful shape. Richard said, “The greatest thing in the world has happened to me. And I want to share it with you.” Then he reached into his pocket and took out a little vial of psilocybin pills.

That freaked me out a little bit, because I was sufficiently straight that I didn't even drink coffee. But I took one, and we sat there in a little cafe, and at some point I was aware of brighter colors and the beauty of things.

My French wasn't that good; I’d been living in Paris for eight months, but I was never able really to capture that kind of casual conversation you hear when people pass by. Suddenly I was aware that I could understand what the people behind me and at other tables were talking about.

It was distracting, and I said, “This is too much for me.”

Richard replied, “You know, this is really too much for me too.”

So we retreated to my fifth-floor walk-up apartment, and I spent the next few hours learning that my worldview had been somewhat limited.

That fall, I went off to Stanford graduate school. I had two offers pending: One was to be inducted into the military and go to Vietnam, and the other was to go to graduate school. I considered both evils, but I took very much the lesser of two.

What you have to understand is that the psychedelic experience made people very unwilling to do things like go to Vietnam, as well as support war in general. We questioned conventional education and we questioned conventional responsibilities, including jobs. That was terrifying to the mainstream of America, and correctly so.

I ended up at Stanford in what seemed like an insanely boring course taught by Willis Harmon. But that course led to a high-dose LSD session in which my world was forever transformed — a kind of classic mystical experience.

In 1962, Michael Murphy invited Willis Harmon to teach at Esalen and Willis took me along. If I remember correctly, the level of psychedelic understanding amongst the people in our seminar was very, very low. No one had any psychedelic experience. Probably some of them had read Huxley's book, The Doors of Perception. There was an interest; whatever was out there in the media was certainly exciting. I think Cary Grant had perhaps gone public by then [the actor admitted he dropped acid an estimated 100 times and that LSD changed his life], but in fact, there was no illegal LSD available for use. Psilocybin was still a mysterious substance that grew in the depths of Mexico and also had been synthesized by Sandoz Laboratories.

On the scientific side, LSD was the most researched psychiatric drug in the world during the early 60s. When I started working at the International Foundation for Advanced Study in Menlo Park, of which Willis Harmon was an advisor and I was their psychology student, I wrote Sandoz Laboratories and said, “Hey, is there any information on LSD?” And they sent me two volumes of the first thousand papers that had been written. So there was very much a two-tiered world.

Sandoz had a problem: They had this incredibly exciting drug — the most powerful substance, molecule for molecule, that had ever been discovered that affected the human mind by a factor of a thousand or so — and yet they couldn't figure out how to make money out of it. Sandoz basically sent it to people who asked for it with the flimsiest of credentials. They would give it to psychotherapists, physicians, hospitals, animal researchers, even, you know, fish researchers. Essentially, Sandoz would respond to all inquiries with something like, “Dear Researcher, Here is the LSD you asked for. Please tell us what you're using it for and how you're doing it. And by the way, we recommend you try it once first.”

I met Michael that first weekend that Willis and I taught there. He and I became terribly close. There was just an enormous rapport. When I got married a couple of years later, Michael agreed that we could use Esalen for the wedding. Of course, we jumped at the chance. I still have an illuminated piece of paper, like a little medieval miniature, that says, “Dorothy and James Fadmian have unlimited use of the baths for this lifetime.” And that was signed by Michael and Richard Price.

Esalen was a very liberated place in those days with lots of sex, lots of nudity, and lots of radical thinking quite beyond the realm of psychedelics. There was the radicalism of Dick Price on the psychodynamic level — with Gestalt on the one hand and encounter groups on the other. Then you had Michael, whose intellectual and philosophical openness was just remarkable. Michael would have B.F. Skinner come for the weekend simply because he wanted to know what he had to say.

The ethos of the baths — of seeing a bunch of people naked — was culturally quite radical. I have several memories of taking someone down to the baths, knowing full well that this was going to be very — not upsetting, but kind of opening. I remember one case in particular, someone went to the baths, came back to their room, and then didn't sleep all night. They just had enormous emotional rushes at what they had just experienced. Not only seeing other people nude, but being one of them.

As to whether psychedelics influenced how things played out at Esalen, or in America in the 60s, I’ll say this: Psychedelics don't have an ideology any more than ice cream has an ideology. People like ice cream and people don't like ice cream, but nobody makes a political statement about it.

When you have something that changes your point of view or your worldview, the rest of your life has to rearrange itself so that things make sense. When nice white kids went down south during the Civil Rights era, they came back changed because they'd had a number of very powerful, emotional experiences that totally revised their view of other people and themselves. There's even a rumor that that's the purpose of undergraduate education — to make these profound changes but kind of slowly, over a number of years. Psychedelics tend to do them quickly. But that’s not a bad thing.

Nobody's bad for not liking psychedelics, or hopelessly depraved if they do. Because psychedelics are basically experiential at the level where concepts aren't very useful.

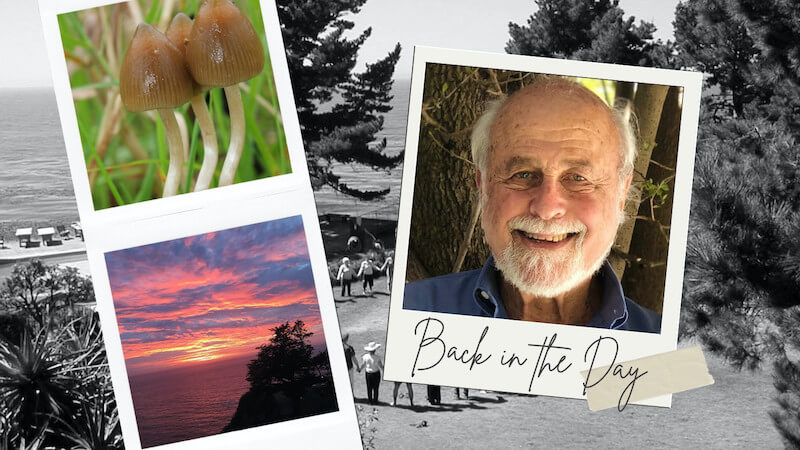

When you look at a sunset, you don't apply concepts.

“Remembering to be as self compassionate as I can and praying to the divine that we're all a part of.”

–Aaron

“Prayer, reading, meditation, walking.”

–Karen

“Erratically — which is an ongoing stream of practice to find peace.”

–Charles

“Try on a daily basis to be kind to myself and to realize that making mistakes is a part of the human condition. Learning from our mistakes is a journey. But it starts with compassion and caring. First for oneself.”

–Steve

“Physically: aerobic exercise, volleyball, ice hockey, cycling, sailing. Emotionally: unfortunately I have to work to ‘not care’ about people or situations which may end painfully. Along the lines of ‘attachment is the source of suffering’, so best to avoid it or limit its scope. Sad though because it could also be the source of great joy. Is it worth the risk?“

–Rainer

“It's time for my heart to be nurtured on one level yet contained on another. To go easy on me and to allow my feelings to be validated, not judged harshly. On the other hand, to let the heart rule with equanimity and not lead the mind and body around like a master.”

–Suzanne

“I spend time thinking of everything I am grateful for, and I try to develop my ability to express compassion for myself and others without reservation. I take time to do the things I need to do to keep myself healthy and happy. This includes taking experiential workshops, fostering relationships, and participating within groups which have a similar interest to become a more compassionate and fulfilled being.“

–Peter

“Self-forgiveness for my own judgments. And oh yeah, coming to Esalen.”

–David B.

“Hmm, this is a tough one! I guess I take care of my heart through fostering relationships with people I feel connected to. Spending quality time with them (whether we're on the phone, through messages/letters, on Zoom, or in-person). Being there for them, listening to them, sharing what's going on with me, my struggles and my successes... like we do in the Esalen weekly Friends of Esalen Zoom sessions!”

–Lori

“I remind myself in many ways of the fact that " Love is all there is!" LOVE is the prize and this one precious life is the stage we get to learn our lessons. I get out into nature, hike, camp, river kayak, fly fish, garden, I create, I dance (not enough!), and I remain grateful for each day, each breath, each moment. Being in the moment, awake, and remembering the gift of life and my feeling of gratitude for all of creation.”

–Steven

“My physical heart by limiting stress and eating a heart-healthy diet. My emotional heart by staying in love with the world and by knowing that all disappointment and loss will pass.“

–David Z.

Today, September 29, is World Heart Day. Strike up a conversation with your own heart and as you feel comfortable, encourage others to do the same. As part of our own transformations and self-care, we sometimes ask for others to illuminate and enliven our hearts or speak our love language.

What if we could do this for ourselves too, even if just for today… or to start a heart practice, forever?

Fadiman will teach Microdosing: The Safe, Surprising, and Emerging Psychedelic Frontier with Adam Bramlage, January 13–15, 2023. The on-campus weekend workshop is sold out, but you can tune in online Saturday, January 14.

Sam Stern is the host of the Voices of Esalen podcast. He lives in Big Sur with his wife, Candice, and a magnificent three-year-old, Roxy.

In the fall of 1962, Jim Fadiman became one of Esalen’s first workshop leaders with his course “The Expanding Vision,” co-taught with Willis Harmon. Fadiman has had a lifelong association with the institute ever since. World-renowned for his research on microdosing psychedelics, he has appeared in countless films as a leading authority on the subject, including Science and Sacraments (2013) and Inside LSD. (2009). His books include The Psychedelic Explorer's Guide: Safe, Therapeutic, and Sacred Journeys, Be Love Now, Essential Sufism, and The Other Side of Haight.

I graduated from Harvard in 1960. I was boringly straight, repressed, and sarcastic, not untypical of a Harvard student. I was also the teacher's pet of a professor named Richard Alpert. During the summer of 1961, I was living in Paris, writing a remarkably bad novel, and Richard passed through on his way to Copenhagen, where he, Timothy Leary, and Aldous Huxley were presenting the Harvard psilocybin research up to that point.

We spent an evening together, and he was just in wonderful shape. Richard said, “The greatest thing in the world has happened to me. And I want to share it with you.” Then he reached into his pocket and took out a little vial of psilocybin pills.

That freaked me out a little bit, because I was sufficiently straight that I didn't even drink coffee. But I took one, and we sat there in a little cafe, and at some point I was aware of brighter colors and the beauty of things.

My French wasn't that good; I’d been living in Paris for eight months, but I was never able really to capture that kind of casual conversation you hear when people pass by. Suddenly I was aware that I could understand what the people behind me and at other tables were talking about.

It was distracting, and I said, “This is too much for me.”

Richard replied, “You know, this is really too much for me too.”

So we retreated to my fifth-floor walk-up apartment, and I spent the next few hours learning that my worldview had been somewhat limited.

That fall, I went off to Stanford graduate school. I had two offers pending: One was to be inducted into the military and go to Vietnam, and the other was to go to graduate school. I considered both evils, but I took very much the lesser of two.

What you have to understand is that the psychedelic experience made people very unwilling to do things like go to Vietnam, as well as support war in general. We questioned conventional education and we questioned conventional responsibilities, including jobs. That was terrifying to the mainstream of America, and correctly so.

I ended up at Stanford in what seemed like an insanely boring course taught by Willis Harmon. But that course led to a high-dose LSD session in which my world was forever transformed — a kind of classic mystical experience.

In 1962, Michael Murphy invited Willis Harmon to teach at Esalen and Willis took me along. If I remember correctly, the level of psychedelic understanding amongst the people in our seminar was very, very low. No one had any psychedelic experience. Probably some of them had read Huxley's book, The Doors of Perception. There was an interest; whatever was out there in the media was certainly exciting. I think Cary Grant had perhaps gone public by then [the actor admitted he dropped acid an estimated 100 times and that LSD changed his life], but in fact, there was no illegal LSD available for use. Psilocybin was still a mysterious substance that grew in the depths of Mexico and also had been synthesized by Sandoz Laboratories.

On the scientific side, LSD was the most researched psychiatric drug in the world during the early 60s. When I started working at the International Foundation for Advanced Study in Menlo Park, of which Willis Harmon was an advisor and I was their psychology student, I wrote Sandoz Laboratories and said, “Hey, is there any information on LSD?” And they sent me two volumes of the first thousand papers that had been written. So there was very much a two-tiered world.

Sandoz had a problem: They had this incredibly exciting drug — the most powerful substance, molecule for molecule, that had ever been discovered that affected the human mind by a factor of a thousand or so — and yet they couldn't figure out how to make money out of it. Sandoz basically sent it to people who asked for it with the flimsiest of credentials. They would give it to psychotherapists, physicians, hospitals, animal researchers, even, you know, fish researchers. Essentially, Sandoz would respond to all inquiries with something like, “Dear Researcher, Here is the LSD you asked for. Please tell us what you're using it for and how you're doing it. And by the way, we recommend you try it once first.”

I met Michael that first weekend that Willis and I taught there. He and I became terribly close. There was just an enormous rapport. When I got married a couple of years later, Michael agreed that we could use Esalen for the wedding. Of course, we jumped at the chance. I still have an illuminated piece of paper, like a little medieval miniature, that says, “Dorothy and James Fadmian have unlimited use of the baths for this lifetime.” And that was signed by Michael and Richard Price.

Esalen was a very liberated place in those days with lots of sex, lots of nudity, and lots of radical thinking quite beyond the realm of psychedelics. There was the radicalism of Dick Price on the psychodynamic level — with Gestalt on the one hand and encounter groups on the other. Then you had Michael, whose intellectual and philosophical openness was just remarkable. Michael would have B.F. Skinner come for the weekend simply because he wanted to know what he had to say.

The ethos of the baths — of seeing a bunch of people naked — was culturally quite radical. I have several memories of taking someone down to the baths, knowing full well that this was going to be very — not upsetting, but kind of opening. I remember one case in particular, someone went to the baths, came back to their room, and then didn't sleep all night. They just had enormous emotional rushes at what they had just experienced. Not only seeing other people nude, but being one of them.

As to whether psychedelics influenced how things played out at Esalen, or in America in the 60s, I’ll say this: Psychedelics don't have an ideology any more than ice cream has an ideology. People like ice cream and people don't like ice cream, but nobody makes a political statement about it.

When you have something that changes your point of view or your worldview, the rest of your life has to rearrange itself so that things make sense. When nice white kids went down south during the Civil Rights era, they came back changed because they'd had a number of very powerful, emotional experiences that totally revised their view of other people and themselves. There's even a rumor that that's the purpose of undergraduate education — to make these profound changes but kind of slowly, over a number of years. Psychedelics tend to do them quickly. But that’s not a bad thing.

Nobody's bad for not liking psychedelics, or hopelessly depraved if they do. Because psychedelics are basically experiential at the level where concepts aren't very useful.

When you look at a sunset, you don't apply concepts.

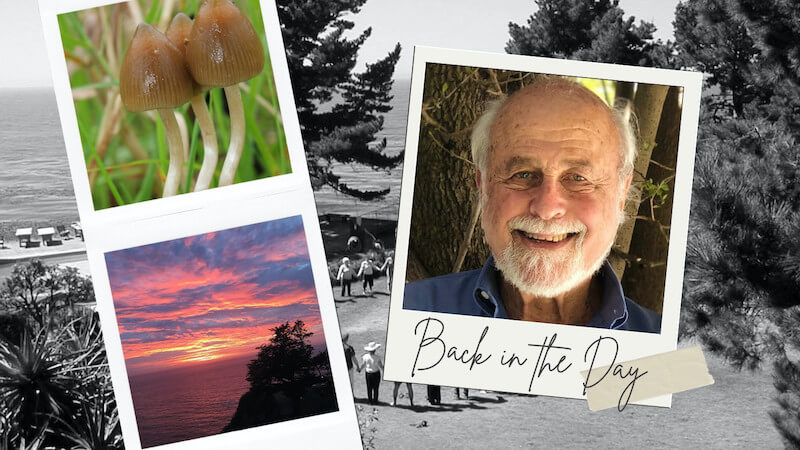

Photo of Psilocybe semilanceata, credit: Alan Rockefeller, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

“Remembering to be as self compassionate as I can and praying to the divine that we're all a part of.”

–Aaron

“Prayer, reading, meditation, walking.”

–Karen

“Erratically — which is an ongoing stream of practice to find peace.”

–Charles

“Try on a daily basis to be kind to myself and to realize that making mistakes is a part of the human condition. Learning from our mistakes is a journey. But it starts with compassion and caring. First for oneself.”

–Steve

“Physically: aerobic exercise, volleyball, ice hockey, cycling, sailing. Emotionally: unfortunately I have to work to ‘not care’ about people or situations which may end painfully. Along the lines of ‘attachment is the source of suffering’, so best to avoid it or limit its scope. Sad though because it could also be the source of great joy. Is it worth the risk?“

–Rainer

“It's time for my heart to be nurtured on one level yet contained on another. To go easy on me and to allow my feelings to be validated, not judged harshly. On the other hand, to let the heart rule with equanimity and not lead the mind and body around like a master.”

–Suzanne

“I spend time thinking of everything I am grateful for, and I try to develop my ability to express compassion for myself and others without reservation. I take time to do the things I need to do to keep myself healthy and happy. This includes taking experiential workshops, fostering relationships, and participating within groups which have a similar interest to become a more compassionate and fulfilled being.“

–Peter

“Self-forgiveness for my own judgments. And oh yeah, coming to Esalen.”

–David B.

“Hmm, this is a tough one! I guess I take care of my heart through fostering relationships with people I feel connected to. Spending quality time with them (whether we're on the phone, through messages/letters, on Zoom, or in-person). Being there for them, listening to them, sharing what's going on with me, my struggles and my successes... like we do in the Esalen weekly Friends of Esalen Zoom sessions!”

–Lori

“I remind myself in many ways of the fact that " Love is all there is!" LOVE is the prize and this one precious life is the stage we get to learn our lessons. I get out into nature, hike, camp, river kayak, fly fish, garden, I create, I dance (not enough!), and I remain grateful for each day, each breath, each moment. Being in the moment, awake, and remembering the gift of life and my feeling of gratitude for all of creation.”

–Steven

“My physical heart by limiting stress and eating a heart-healthy diet. My emotional heart by staying in love with the world and by knowing that all disappointment and loss will pass.“

–David Z.

Today, September 29, is World Heart Day. Strike up a conversation with your own heart and as you feel comfortable, encourage others to do the same. As part of our own transformations and self-care, we sometimes ask for others to illuminate and enliven our hearts or speak our love language.

What if we could do this for ourselves too, even if just for today… or to start a heart practice, forever?

Fadiman will teach Microdosing: The Safe, Surprising, and Emerging Psychedelic Frontier with Adam Bramlage, January 13–15, 2023. The on-campus weekend workshop is sold out, but you can tune in online Saturday, January 14.

In the fall of 1962, Jim Fadiman became one of Esalen’s first workshop leaders with his course “The Expanding Vision,” co-taught with Willis Harmon. Fadiman has had a lifelong association with the institute ever since. World-renowned for his research on microdosing psychedelics, he has appeared in countless films as a leading authority on the subject, including Science and Sacraments (2013) and Inside LSD. (2009). His books include The Psychedelic Explorer's Guide: Safe, Therapeutic, and Sacred Journeys, Be Love Now, Essential Sufism, and The Other Side of Haight.

I graduated from Harvard in 1960. I was boringly straight, repressed, and sarcastic, not untypical of a Harvard student. I was also the teacher's pet of a professor named Richard Alpert. During the summer of 1961, I was living in Paris, writing a remarkably bad novel, and Richard passed through on his way to Copenhagen, where he, Timothy Leary, and Aldous Huxley were presenting the Harvard psilocybin research up to that point.

We spent an evening together, and he was just in wonderful shape. Richard said, “The greatest thing in the world has happened to me. And I want to share it with you.” Then he reached into his pocket and took out a little vial of psilocybin pills.

That freaked me out a little bit, because I was sufficiently straight that I didn't even drink coffee. But I took one, and we sat there in a little cafe, and at some point I was aware of brighter colors and the beauty of things.

My French wasn't that good; I’d been living in Paris for eight months, but I was never able really to capture that kind of casual conversation you hear when people pass by. Suddenly I was aware that I could understand what the people behind me and at other tables were talking about.

It was distracting, and I said, “This is too much for me.”

Richard replied, “You know, this is really too much for me too.”

So we retreated to my fifth-floor walk-up apartment, and I spent the next few hours learning that my worldview had been somewhat limited.

That fall, I went off to Stanford graduate school. I had two offers pending: One was to be inducted into the military and go to Vietnam, and the other was to go to graduate school. I considered both evils, but I took very much the lesser of two.

What you have to understand is that the psychedelic experience made people very unwilling to do things like go to Vietnam, as well as support war in general. We questioned conventional education and we questioned conventional responsibilities, including jobs. That was terrifying to the mainstream of America, and correctly so.

I ended up at Stanford in what seemed like an insanely boring course taught by Willis Harmon. But that course led to a high-dose LSD session in which my world was forever transformed — a kind of classic mystical experience.

In 1962, Michael Murphy invited Willis Harmon to teach at Esalen and Willis took me along. If I remember correctly, the level of psychedelic understanding amongst the people in our seminar was very, very low. No one had any psychedelic experience. Probably some of them had read Huxley's book, The Doors of Perception. There was an interest; whatever was out there in the media was certainly exciting. I think Cary Grant had perhaps gone public by then [the actor admitted he dropped acid an estimated 100 times and that LSD changed his life], but in fact, there was no illegal LSD available for use. Psilocybin was still a mysterious substance that grew in the depths of Mexico and also had been synthesized by Sandoz Laboratories.

On the scientific side, LSD was the most researched psychiatric drug in the world during the early 60s. When I started working at the International Foundation for Advanced Study in Menlo Park, of which Willis Harmon was an advisor and I was their psychology student, I wrote Sandoz Laboratories and said, “Hey, is there any information on LSD?” And they sent me two volumes of the first thousand papers that had been written. So there was very much a two-tiered world.

Sandoz had a problem: They had this incredibly exciting drug — the most powerful substance, molecule for molecule, that had ever been discovered that affected the human mind by a factor of a thousand or so — and yet they couldn't figure out how to make money out of it. Sandoz basically sent it to people who asked for it with the flimsiest of credentials. They would give it to psychotherapists, physicians, hospitals, animal researchers, even, you know, fish researchers. Essentially, Sandoz would respond to all inquiries with something like, “Dear Researcher, Here is the LSD you asked for. Please tell us what you're using it for and how you're doing it. And by the way, we recommend you try it once first.”

I met Michael that first weekend that Willis and I taught there. He and I became terribly close. There was just an enormous rapport. When I got married a couple of years later, Michael agreed that we could use Esalen for the wedding. Of course, we jumped at the chance. I still have an illuminated piece of paper, like a little medieval miniature, that says, “Dorothy and James Fadmian have unlimited use of the baths for this lifetime.” And that was signed by Michael and Richard Price.

Esalen was a very liberated place in those days with lots of sex, lots of nudity, and lots of radical thinking quite beyond the realm of psychedelics. There was the radicalism of Dick Price on the psychodynamic level — with Gestalt on the one hand and encounter groups on the other. Then you had Michael, whose intellectual and philosophical openness was just remarkable. Michael would have B.F. Skinner come for the weekend simply because he wanted to know what he had to say.

The ethos of the baths — of seeing a bunch of people naked — was culturally quite radical. I have several memories of taking someone down to the baths, knowing full well that this was going to be very — not upsetting, but kind of opening. I remember one case in particular, someone went to the baths, came back to their room, and then didn't sleep all night. They just had enormous emotional rushes at what they had just experienced. Not only seeing other people nude, but being one of them.

As to whether psychedelics influenced how things played out at Esalen, or in America in the 60s, I’ll say this: Psychedelics don't have an ideology any more than ice cream has an ideology. People like ice cream and people don't like ice cream, but nobody makes a political statement about it.

When you have something that changes your point of view or your worldview, the rest of your life has to rearrange itself so that things make sense. When nice white kids went down south during the Civil Rights era, they came back changed because they'd had a number of very powerful, emotional experiences that totally revised their view of other people and themselves. There's even a rumor that that's the purpose of undergraduate education — to make these profound changes but kind of slowly, over a number of years. Psychedelics tend to do them quickly. But that’s not a bad thing.

Nobody's bad for not liking psychedelics, or hopelessly depraved if they do. Because psychedelics are basically experiential at the level where concepts aren't very useful.

When you look at a sunset, you don't apply concepts.

“Remembering to be as self compassionate as I can and praying to the divine that we're all a part of.”

–Aaron

“Prayer, reading, meditation, walking.”

–Karen

“Erratically — which is an ongoing stream of practice to find peace.”

–Charles

“Try on a daily basis to be kind to myself and to realize that making mistakes is a part of the human condition. Learning from our mistakes is a journey. But it starts with compassion and caring. First for oneself.”

–Steve

“Physically: aerobic exercise, volleyball, ice hockey, cycling, sailing. Emotionally: unfortunately I have to work to ‘not care’ about people or situations which may end painfully. Along the lines of ‘attachment is the source of suffering’, so best to avoid it or limit its scope. Sad though because it could also be the source of great joy. Is it worth the risk?“

–Rainer

“It's time for my heart to be nurtured on one level yet contained on another. To go easy on me and to allow my feelings to be validated, not judged harshly. On the other hand, to let the heart rule with equanimity and not lead the mind and body around like a master.”

–Suzanne

“I spend time thinking of everything I am grateful for, and I try to develop my ability to express compassion for myself and others without reservation. I take time to do the things I need to do to keep myself healthy and happy. This includes taking experiential workshops, fostering relationships, and participating within groups which have a similar interest to become a more compassionate and fulfilled being.“

–Peter

“Self-forgiveness for my own judgments. And oh yeah, coming to Esalen.”

–David B.

“Hmm, this is a tough one! I guess I take care of my heart through fostering relationships with people I feel connected to. Spending quality time with them (whether we're on the phone, through messages/letters, on Zoom, or in-person). Being there for them, listening to them, sharing what's going on with me, my struggles and my successes... like we do in the Esalen weekly Friends of Esalen Zoom sessions!”

–Lori

“I remind myself in many ways of the fact that " Love is all there is!" LOVE is the prize and this one precious life is the stage we get to learn our lessons. I get out into nature, hike, camp, river kayak, fly fish, garden, I create, I dance (not enough!), and I remain grateful for each day, each breath, each moment. Being in the moment, awake, and remembering the gift of life and my feeling of gratitude for all of creation.”

–Steven

“My physical heart by limiting stress and eating a heart-healthy diet. My emotional heart by staying in love with the world and by knowing that all disappointment and loss will pass.“

–David Z.

Today, September 29, is World Heart Day. Strike up a conversation with your own heart and as you feel comfortable, encourage others to do the same. As part of our own transformations and self-care, we sometimes ask for others to illuminate and enliven our hearts or speak our love language.

What if we could do this for ourselves too, even if just for today… or to start a heart practice, forever?

Fadiman will teach Microdosing: The Safe, Surprising, and Emerging Psychedelic Frontier with Adam Bramlage, January 13–15, 2023. The on-campus weekend workshop is sold out, but you can tune in online Saturday, January 14.

Sam Stern is the host of the Voices of Esalen podcast. He lives in Big Sur with his wife, Candice, and a magnificent three-year-old, Roxy.